Adsorption Energies#

Pre-trained ODAC models are versatile across various MOF-related tasks. To begin, we’ll start with a fundamental application: calculating the adsorption energy for a single CO2 molecule. This serves as an excellent and simple demonstration of what you can achieve with these datasets and models.

For predicting the adsorption energy of a single CO2 molecule within a MOF structure, the adsorption energy (\(E_{\mathrm{ads}}\)) is defined as:

Each term on the right-hand side represents the energy of the relaxed state of the indicated chemical system. For a comprehensive understanding of our methodology for computing these adsorption energies, please refer to our paper.

Loading Pre-trained Models#

Need to install fairchem-core or get UMA access or getting permissions/401 errors?

Install the necessary packages using pip, uv etc

Get access to any necessary huggingface gated models

Get and login to your Huggingface account

Request access to https://huggingface.co/facebook/UMA

Create a Huggingface token at https://huggingface.co/settings/tokens/ with the permission “Permissions: Read access to contents of all public gated repos you can access”

Add the token as an environment variable using

huggingface-cli loginor by setting the HF_TOKEN environment variable.

A pre-trained model can be loaded using FAIRChemCalculator. In this example, we’ll employ UMA to determine the CO2 adsorption energies.

from fairchem.core import FAIRChemCalculator, pretrained_mlip

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1p1")

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="odac")

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

Adsorption in rigid MOFs: CO2 Adsorption Energy in Mg-MOF-74#

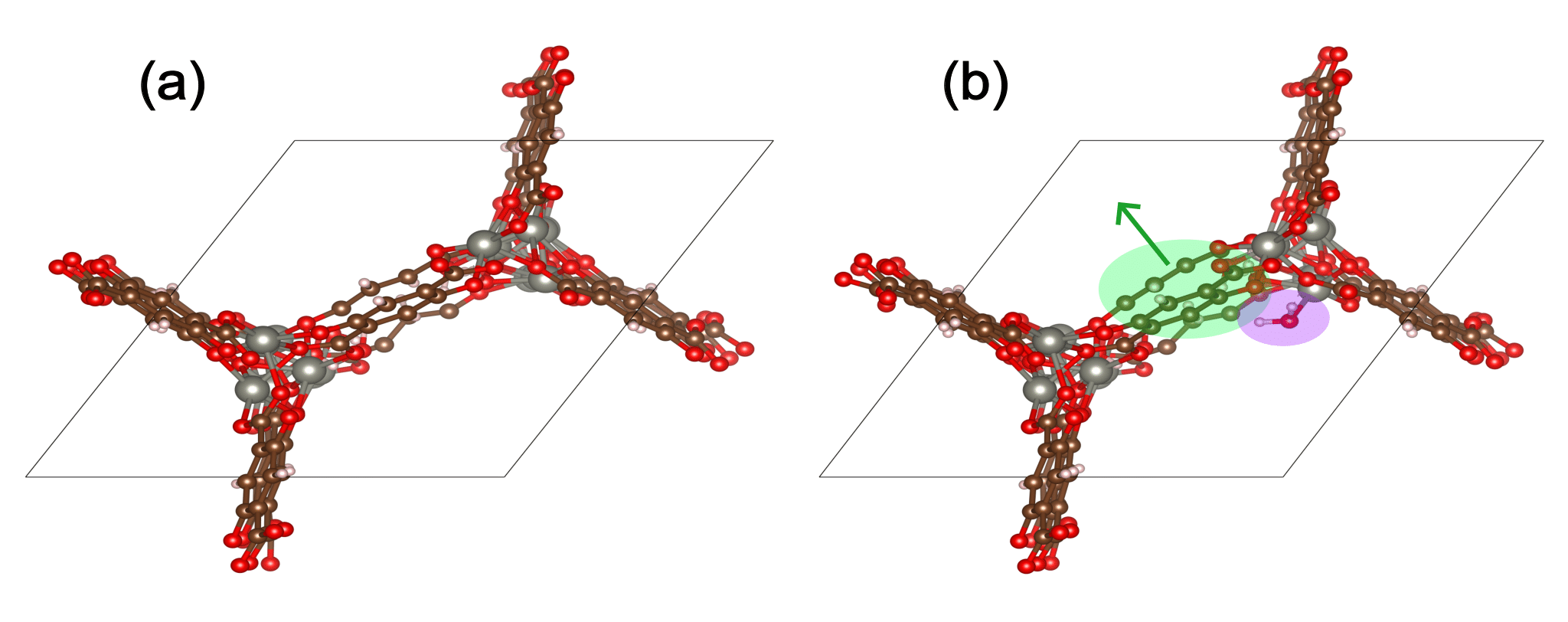

Let’s apply our knowledge to Mg-MOF-74, a widely studied MOF known for its excellent CO2 adsorption properties. Its structure comprises magnesium atomic complexes connected by a carboxylated and oxidized benzene ring, serving as an organic linker. Previous studies consistently report the CO2 adsorption energy for Mg-MOF-74 to be around -0.40 eV [1] [2] [3].

Our goal is to verify if we can achieve a similar value by performing a simple single-point calculation using UMA. In the ODAC23 dataset, all MOF structures are identified by their CSD (Cambridge Structural Database) code. For Mg-MOF-74, this code is OPAGIX. We’ve extracted a specific OPAGIX+CO2 configuration from the dataset, which exhibits the lowest adsorption energy among its counterparts.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from ase.io import read

from ase.visualize.plot import plot_atoms

mof_co2 = read("structures/OPAGIX_w_CO2.cif")

mof = read("structures/OPAGIX.cif")

co2 = read("structures/co2.xyz")

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5, 4.5), dpi=250)

plot_atoms(mof_co2, ax)

ax.set_axis_off()

The final step in calculating the adsorption energy involves connecting the FAIRChemCalculator to each relaxed structure: OPAGIX+CO2, OPAGIX, and CO2. The structures used here are already relaxed from ODAC23. For simplicity, we assume here that further relaxations can be neglected. We will show how to go beyond this assumption in the next section.

mof_co2.calc = calc

mof.calc = calc

co2.calc = calc

E_ads = (

mof_co2.get_potential_energy()

- mof.get_potential_energy()

- co2.get_potential_energy()

)

print(f"Adsorption energy of CO2 in Mg-MOF-74: {E_ads:.3f} eV")

Adsorption energy of CO2 in Mg-MOF-74: -0.459 eV

Adsorption in flexible MOFs#

The adsorption energy calculation method outlined above is typically performed with rigid MOFs for simplicity. Both experimental and modeling literature have shown, however, that MOF flexibility can be important in accurately capturing the underlying chemistry of adsorption [1] [2] [3]. In particular, uptake can be improved by treating MOFs as flexible. Two types of MOF flexibility can be considered: intrinsic flexibility and deformation induced by guest molecules. In the Open DAC Project, we consider the latter MOF deformation by allowing the atomic positions of the MOF to relax during geometry optimization [4]. The addition of additional degrees of freedoms can complicate the computation of the adsorption energy and necessitates an extra step in the calculation procedure.

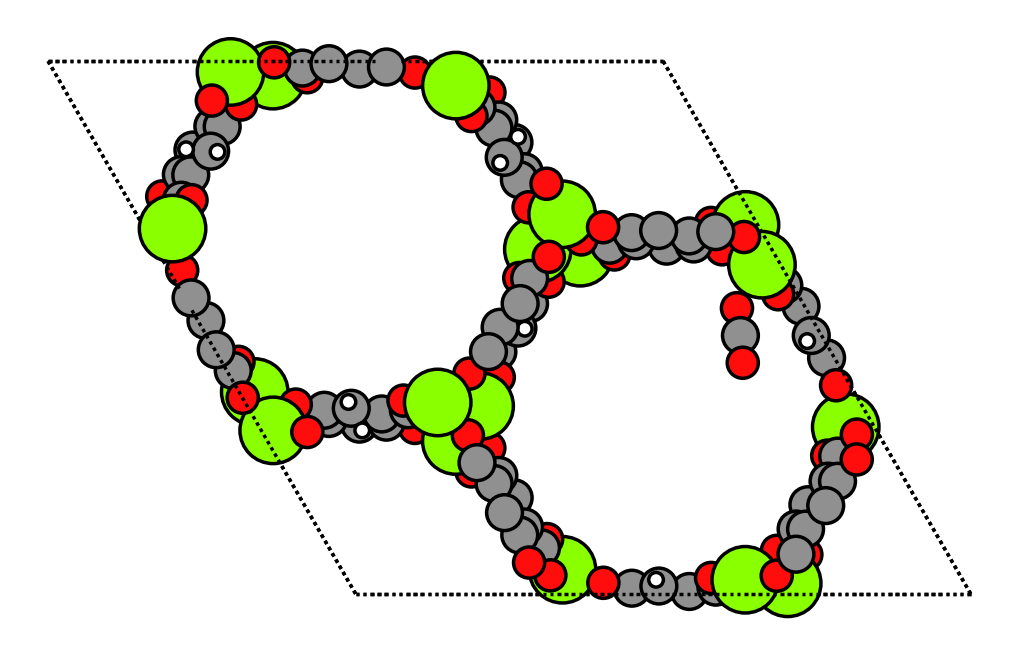

The figure below shows water adsorption in the MOF with CSD code WOBHEB with added defects (WOBHEB_0.11_0) from a DFT simulation. A typical adsorption energy calculation would only seek to capture the effects shaded in purple, which include both chemisorption and non-bonded interactions between the host and guest molecule. When allowing the MOF to relax, however, the adsorption energy also includes the energetic effect of the MOF deformation highlighted in green.

To account for this deformation, it is vital to use the most energetically favorable MOF geometry for the empty MOF term in Eqn. 1. Including MOF atomic coordinates as degrees of freedom can result in three possible outcomes:

The MOF does not deform, so the energies of the relaxed empty MOF and the MOF in the adsorbed state are the same

The MOF deforms to a less energetically favorable geometry than its ground state

The MOF locates a new energetically favorable geoemtry relative to the empty MOF relaxation

The first outcome requires no additional computation because the MOF rigidity assumption is valid. The second outcome represents physical and reversible deformation where the MOF returns to its empty ground state upon removal of the guest molecule. The third outcome is often the result of the guest molecule breaking local symmetry. We also found cases in ODAC in which both outcomes 2 and 3 occur within the same MOF.

To ensure the most energetically favorable empty MOF geometry is found, an addition empty MOF relaxation should be performed after MOF + adsorbate relaxation. The guest molecule should be removed, and the MOF should be relaxed starting from its geometry in the adsorbed state. If all deformation is reversible, the MOF will return to its original empty geometry. Otherwise, the lowest energy (most favorable) MOF geometry should be taken as the reference energy, \(E_{\mathrm{MOF}}\), in Eqn. 1.

H2O Adsorption Energy in Flexible WOBHEB with UMA#

The first part of this tutorial demonstrates how to perform a single point adsorption energy calculation using UMA. To treat MOFs as flexible, we perform all calculations on geometries determined by geometry optimization. The following example corresponds to the figure shown above (H2O adsorption in WOBHEB_0.11_0).

In this tutorial, \(E_{x}(r_{y})\) corresponds to the energy of \(x\) determined from geometry optimization of \(y\).

First, we obtain the energy of the empty MOF from relaxation of only the MOF: \(E_{\mathrm{MOF}}(r_{\mathrm{MOF}})\)

import ase.io

from ase.optimize import BFGS

mof = ase.io.read("structures/WOBHEB_0.11.cif")

mof.calc = calc

relax = BFGS(mof)

relax.run(fmax=0.05)

E_mof_empty = mof.get_potential_energy()

print(f"Energy of empty MOF: {E_mof_empty:.3f} eV")

Step Time Energy fmax

BFGS: 0 21:30:28 -1077.274065 0.206406

BFGS: 1 21:30:28 -1077.276780 0.152729

BFGS: 2 21:30:28 -1077.281942 0.169926

BFGS: 3 21:30:29 -1077.284767 0.155780

BFGS: 4 21:30:29 -1077.288837 0.108783

BFGS: 5 21:30:29 -1077.291024 0.086440

BFGS: 6 21:30:29 -1077.293360 0.093430

BFGS: 7 21:30:30 -1077.295415 0.100107

BFGS: 8 21:30:30 -1077.297831 0.102532

BFGS: 9 21:30:30 -1077.300015 0.091597

BFGS: 10 21:30:30 -1077.302011 0.079035

BFGS: 11 21:30:31 -1077.304135 0.105570

BFGS: 12 21:30:31 -1077.306723 0.087946

BFGS: 13 21:30:31 -1077.309518 0.086344

BFGS: 14 21:30:31 -1077.312257 0.086879

BFGS: 15 21:30:32 -1077.314705 0.106270

BFGS: 16 21:30:32 -1077.316991 0.106218

BFGS: 17 21:30:32 -1077.319476 0.085499

BFGS: 18 21:30:32 -1077.322264 0.109641

BFGS: 19 21:30:32 -1077.325136 0.148715

BFGS: 20 21:30:33 -1077.327763 0.125900

BFGS: 21 21:30:33 -1077.329927 0.069113

BFGS: 22 21:30:33 -1077.331950 0.087285

BFGS: 23 21:30:33 -1077.334270 0.125227

BFGS: 24 21:30:34 -1077.336834 0.166688

BFGS: 25 21:30:34 -1077.339540 0.145587

BFGS: 26 21:30:34 -1077.342151 0.087653

BFGS: 27 21:30:34 -1077.344539 0.076211

BFGS: 28 21:30:35 -1077.346896 0.148965

BFGS: 29 21:30:35 -1077.349785 0.170254

BFGS: 30 21:30:35 -1077.352530 0.109292

BFGS: 31 21:30:35 -1077.354750 0.070334

BFGS: 32 21:30:36 -1077.356776 0.089700

BFGS: 33 21:30:36 -1077.358659 0.124292

BFGS: 34 21:30:36 -1077.360599 0.108075

BFGS: 35 21:30:36 -1077.362469 0.068608

BFGS: 36 21:30:37 -1077.364168 0.070196

BFGS: 37 21:30:37 -1077.365715 0.105437

BFGS: 38 21:30:37 -1077.367257 0.104263

BFGS: 39 21:30:37 -1077.368771 0.062811

BFGS: 40 21:30:38 -1077.370140 0.057147

BFGS: 41 21:30:38 -1077.371373 0.061211

BFGS: 42 21:30:38 -1077.372442 0.064290

BFGS: 43 21:30:38 -1077.373408 0.058055

BFGS: 44 21:30:38 -1077.374353 0.046048

Energy of empty MOF: -1077.374 eV

Next, we add the H2O guest molecule and relax the MOF + adsorbate to obtain \(E_{\mathrm{MOF+H2O}}(r_{\mathrm{MOF+H2O}})\).

mof_h2o = ase.io.read("structures/WOBHEB_H2O.cif")

mof_h2o.calc = calc

relax = BFGS(mof_h2o)

relax.run(fmax=0.05)

E_combo = mof_h2o.get_potential_energy()

print(f"Energy of MOF + H2O: {E_combo:.3f} eV")

Step Time Energy fmax

BFGS: 0 21:30:39 -1091.565590 1.145036

BFGS: 1 21:30:39 -1091.585063 0.314149

BFGS: 2 21:30:39 -1091.590210 0.243429

BFGS: 3 21:30:40 -1091.608170 0.237249

BFGS: 4 21:30:40 -1091.614632 0.227922

BFGS: 5 21:30:40 -1091.625215 0.186791

BFGS: 6 21:30:40 -1091.632359 0.178909

BFGS: 7 21:30:41 -1091.640632 0.175153

BFGS: 8 21:30:41 -1091.648043 0.184535

BFGS: 9 21:30:41 -1091.656148 0.160877

BFGS: 10 21:30:41 -1091.663841 0.178464

BFGS: 11 21:30:42 -1091.672296 0.188705

BFGS: 12 21:30:42 -1091.682091 0.157544

BFGS: 13 21:30:42 -1091.692984 0.177275

BFGS: 14 21:30:42 -1091.704436 0.158175

BFGS: 15 21:30:43 -1091.715512 0.191650

BFGS: 16 21:30:43 -1091.725713 0.197863

BFGS: 17 21:30:43 -1091.735328 0.163703

BFGS: 18 21:30:43 -1091.745540 0.151489

BFGS: 19 21:30:44 -1091.754025 0.170791

BFGS: 20 21:30:44 -1091.761493 0.153505

BFGS: 21 21:30:44 -1091.767893 0.152827

BFGS: 22 21:30:44 -1091.774204 0.166039

BFGS: 23 21:30:45 -1091.780884 0.135366

BFGS: 24 21:30:45 -1091.788358 0.180962

BFGS: 25 21:30:45 -1091.794278 0.204599

BFGS: 26 21:30:45 -1091.800641 0.131411

BFGS: 27 21:30:46 -1091.806525 0.189774

BFGS: 28 21:30:46 -1091.812307 0.199055

BFGS: 29 21:30:46 -1091.817180 0.151640

BFGS: 30 21:30:46 -1091.822212 0.100098

BFGS: 31 21:30:47 -1091.826302 0.125265

BFGS: 32 21:30:47 -1091.832530 0.177271

BFGS: 33 21:30:47 -1091.837114 0.246054

BFGS: 34 21:30:47 -1091.842050 0.112609

BFGS: 35 21:30:48 -1091.845776 0.331225

BFGS: 36 21:30:48 -1091.850861 0.173692

BFGS: 37 21:30:48 -1091.858474 0.159616

BFGS: 38 21:30:48 -1091.865282 0.141868

BFGS: 39 21:30:49 -1091.872008 0.139450

BFGS: 40 21:30:49 -1091.878235 0.267467

BFGS: 41 21:30:49 -1091.879759 0.600384

BFGS: 42 21:30:49 -1091.887485 0.522225

BFGS: 43 21:30:50 -1091.893892 0.249357

BFGS: 44 21:30:50 -1091.900389 0.180958

BFGS: 45 21:30:50 -1091.915807 0.235770

BFGS: 46 21:30:50 -1091.924341 0.386982

BFGS: 47 21:30:51 -1091.937909 0.264421

BFGS: 48 21:30:51 -1091.952902 0.467297

BFGS: 49 21:30:51 -1091.971876 0.642749

BFGS: 50 21:30:51 -1091.970482 1.392366

BFGS: 51 21:30:52 -1092.006084 0.442430

BFGS: 52 21:30:52 -1092.022826 0.280885

BFGS: 53 21:30:52 -1092.070255 0.299186

BFGS: 54 21:30:52 -1092.086442 0.297600

BFGS: 55 21:30:53 -1092.119382 0.639797

BFGS: 56 21:30:53 -1092.123852 0.388005

BFGS: 57 21:30:53 -1092.139129 0.207870

BFGS: 58 21:30:53 -1092.151142 0.259459

BFGS: 59 21:30:54 -1092.168609 0.379455

BFGS: 60 21:30:54 -1092.178893 0.396199

BFGS: 61 21:30:54 -1092.189958 0.329143

BFGS: 62 21:30:54 -1092.200873 0.230602

BFGS: 63 21:30:55 -1092.213025 0.162941

BFGS: 64 21:30:55 -1092.222517 0.180913

BFGS: 65 21:30:55 -1092.230899 0.155001

BFGS: 66 21:30:55 -1092.237170 0.104157

BFGS: 67 21:30:55 -1092.242637 0.110665

BFGS: 68 21:30:56 -1092.248371 0.138767

BFGS: 69 21:30:56 -1092.253427 0.147775

BFGS: 70 21:30:56 -1092.258659 0.121972

BFGS: 71 21:30:56 -1092.263501 0.109480

BFGS: 72 21:30:57 -1092.267531 0.134906

BFGS: 73 21:30:57 -1092.271253 0.147310

BFGS: 74 21:30:57 -1092.274833 0.132684

BFGS: 75 21:30:58 -1092.278150 0.108192

BFGS: 76 21:30:58 -1092.281536 0.094407

BFGS: 77 21:30:58 -1092.284638 0.093898

BFGS: 78 21:30:58 -1092.287078 0.095589

BFGS: 79 21:30:59 -1092.289629 0.080145

BFGS: 80 21:30:59 -1092.291664 0.069954

BFGS: 81 21:30:59 -1092.293483 0.071901

BFGS: 82 21:30:59 -1092.295011 0.082019

BFGS: 83 21:31:00 -1092.296363 0.082774

BFGS: 84 21:31:00 -1092.297791 0.077927

BFGS: 85 21:31:00 -1092.299264 0.082854

BFGS: 86 21:31:00 -1092.301101 0.069568

BFGS: 87 21:31:01 -1092.302698 0.059666

BFGS: 88 21:31:01 -1092.304543 0.054870

BFGS: 89 21:31:01 -1092.306082 0.063356

BFGS: 90 21:31:01 -1092.307463 0.054477

BFGS: 91 21:31:02 -1092.308768 0.052977

BFGS: 92 21:31:02 -1092.309773 0.062237

BFGS: 93 21:31:02 -1092.310670 0.062466

BFGS: 94 21:31:02 -1092.311405 0.055456

BFGS: 95 21:31:03 -1092.312168 0.045535

Energy of MOF + H2O: -1092.312 eV

We can now isolate the MOF atoms from the relaxed MOF + H2O geometry and see that the MOF has adopted a geometry that is less energetically favorable than the empty MOF by ~0.2 eV. The energy of the MOF in the adsorbed state corresponds to \(E_{\mathrm{MOF}}(r_{\mathrm{MOF+H2O}})\).

mof_adsorbed_state = mof_h2o[:-3]

mof_adsorbed_state.calc = calc

E_mof_adsorbed_state = mof_adsorbed_state.get_potential_energy()

print(f"Energy of MOF in the adsorbed state: {E_mof_adsorbed_state:.3f} eV")

Energy of MOF in the adsorbed state: -1077.091 eV

H2O adsorption in this MOF appears to correspond to Case #2 as outlined above. We can now perform re-relaxation of the empty MOF starting from the \(r_{\mathrm{MOF+H2O}}\) geometry.

relax = BFGS(mof_adsorbed_state)

relax.run(fmax=0.05)

E_mof_rerelax = mof_adsorbed_state.get_potential_energy()

print(f"Energy of re-relaxed empty MOF: {E_mof_rerelax:.3f} eV")

Step Time Energy fmax

BFGS: 0 21:31:03 -1077.090691 0.986969

BFGS: 1 21:31:03 -1077.122893 0.873715

BFGS: 2 21:31:03 -1077.172072 0.819483

BFGS: 3 21:31:04 -1077.210892 0.524544

BFGS: 4 21:31:04 -1077.230394 0.438003

BFGS: 5 21:31:04 -1077.246866 0.281794

BFGS: 6 21:31:04 -1077.257624 0.260275

BFGS: 7 21:31:05 -1077.266911 0.248043

BFGS: 8 21:31:05 -1077.276479 0.223250

BFGS: 9 21:31:05 -1077.283430 0.156201

BFGS: 10 21:31:05 -1077.288376 0.140762

BFGS: 11 21:31:06 -1077.292367 0.136074

BFGS: 12 21:31:06 -1077.295826 0.154850

BFGS: 13 21:31:06 -1077.300804 0.165283

BFGS: 14 21:31:06 -1077.305052 0.147138

BFGS: 15 21:31:07 -1077.309324 0.132472

BFGS: 16 21:31:07 -1077.313259 0.159472

BFGS: 17 21:31:07 -1077.317539 0.162140

BFGS: 18 21:31:07 -1077.322166 0.149846

BFGS: 19 21:31:08 -1077.325868 0.124290

BFGS: 20 21:31:08 -1077.328466 0.117708

BFGS: 21 21:31:08 -1077.330834 0.112576

BFGS: 22 21:31:08 -1077.333397 0.120809

BFGS: 23 21:31:08 -1077.336318 0.113469

BFGS: 24 21:31:09 -1077.339180 0.097609

BFGS: 25 21:31:09 -1077.341477 0.088476

BFGS: 26 21:31:09 -1077.343543 0.081588

BFGS: 27 21:31:09 -1077.345199 0.071557

BFGS: 28 21:31:10 -1077.347012 0.083841

BFGS: 29 21:31:10 -1077.348584 0.100688

BFGS: 30 21:31:10 -1077.350335 0.078066

BFGS: 31 21:31:10 -1077.351653 0.052311

BFGS: 32 21:31:11 -1077.352968 0.061359

BFGS: 33 21:31:11 -1077.354314 0.079768

BFGS: 34 21:31:11 -1077.355733 0.085340

BFGS: 35 21:31:11 -1077.357373 0.074116

BFGS: 36 21:31:12 -1077.358910 0.068620

BFGS: 37 21:31:12 -1077.360228 0.071790

BFGS: 38 21:31:12 -1077.361458 0.074948

BFGS: 39 21:31:12 -1077.362863 0.088109

BFGS: 40 21:31:13 -1077.364020 0.070085

BFGS: 41 21:31:13 -1077.365146 0.052598

BFGS: 42 21:31:13 -1077.366248 0.063836

BFGS: 43 21:31:13 -1077.367380 0.069145

BFGS: 44 21:31:14 -1077.368744 0.079322

BFGS: 45 21:31:15 -1077.370047 0.048332

Energy of re-relaxed empty MOF: -1077.370 eV

The MOF returns to its original empty reference energy upon re-relaxation, confirming that this deformation is physically relevant and is induced by the adsorbate molecule. In Case #3, this re-relaxed energy will be more negative (more favorable) than the original empty MOF relaxation. Thus, we take the reference empty MOF energy (\(E_{\mathrm{MOF}}\) in Eqn. 1) to be the minimum of the original empty MOF energy and the re-relaxed MOf energy:

E_mof = min(E_mof_empty, E_mof_rerelax)

# get adsorbate reference energy

h2o = mof_h2o[-3:]

h2o.calc = calc

E_h2o = h2o.get_potential_energy()

# compute adsorption energy

E_ads = E_combo - E_mof - E_h2o

print(f"Adsorption energy of H2O in WOBHEB_0.11_0: {E_ads:.3f} eV")

Adsorption energy of H2O in WOBHEB_0.11_0: -0.689 eV

This adsorption energy closely matches that from DFT (–0.699 eV) [1]. The strong adsorption energy is a consequence of both H2O chemisorption and MOF deformation. We can decompose the adsorption energy into contributions from these two factors. Assuming rigid H2O molecules, we define \(E_{\mathrm{int}}\) and \(E_{\mathrm{MOF,deform}}\), respectively, as

\(E_{\mathrm{int}}\) describes host host–guest interactions for the MOF in the adsorbed state only. \(E_{\mathrm{MOF,deform}}\) quantifies the magnitude of deformation between the MOF in the adsorbed state and the most energetically favorable empty MOF geometry determined from the workflow presented here. It can be shown that

For H2O adsorption in WOBHEB_0.11, we have

E_int = E_combo - E_mof_adsorbed_state - E_h2o

print(f"E_int: {E_int}")

E_int: -0.9727649092670116

E_mof_deform = E_mof_adsorbed_state - E_mof_empty

print(f"E_mof_deform: {E_mof_deform}")

E_mof_deform: 0.2836618423461914

E_ads = E_int + E_mof_deform

print(f"E_ads: {E_ads}")

E_ads: -0.6891030669208202

\(E_{\mathrm{int}}\) is equivalent to \(E_{\mathrm{ads}}\) when the MOF is assumed to be rigid. In this case, failure to consider adsorbate-induced deformation would result in an overestimation of the adsorption energy magnitude.