UMA Intro Tutorial#

This tutorial will walk you through a few examples of how you can use UMA. Each step is covered in more detail elsewhere in the documentation, but this is well suited to a ~1-2 hour tutorial session for researchers new to UMA but with some background in ASE and molecular simulations.

Before you start / installation#

You need to get a HuggingFace account and request access to the UMA models.

You need a Huggingface account, request access to https://huggingface.co/facebook/UMA, and to create a Huggingface token at https://huggingface.co/settings/tokens/ with these permission:

Permissions: Read access to contents of all public gated repos you can access

Then, add the token as an environment variable (using huggingface-cli login:

# Enter token via huggingface-cli

! huggingface-cli login

or you can set the token via HF_TOKEN variable:

# Set token via env variable

import os

os.environ['HF_TOKEN'] = 'MYTOKEN'

Installation process#

It may be enough to use pip install fairchem-core. This gets you the latest version on PyPi (https://pypi.org/project/fairchem-core/)

Here we install some sub-packages. This can take 2-5 minutes to run.

! pip install fairchem-core fairchem-data-oc fairchem-applications-cattsunami x3dase

# Check that packages are installed

!pip list | grep fairchem

fairchem-applications-cattsunami 1.1.2.dev148+g4c07b0a8

fairchem-core 2.13.1.dev26+g4c07b0a8

fairchem-data-oc 1.0.3.dev148+g4c07b0a8

fairchem-data-omat 0.2.1.dev53+g4c07b0a8

import fairchem.core

fairchem.core.__version__

'2.13.1.dev26+g4c07b0a8'

Illustrative examples#

These should just run, and are here to show some basic uses.

Critical points:

Create a calculator

Specify the task_name

Use calculator like other ASE calculators

Spin gap energy - OMOL#

This is the difference in energy between a triplet and single ground state for a CH2 radical. This downloads a ~1GB checkpoint the first time you run it.

We don’t set a device here, so we get a warning about using a CPU device. You can ignore that. If a CUDA environment is available, a GPU may be used to speed up the calculations.

from fairchem.core import FAIRChemCalculator, pretrained_mlip

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1")

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

from ase.build import molecule

# singlet CH2

singlet = molecule("CH2_s1A1d")

singlet.info.update({"spin": 1, "charge": 0})

singlet.calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omol")

# triplet CH2

triplet = molecule("CH2_s3B1d")

triplet.info.update({"spin": 3, "charge": 0})

triplet.calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omol")

print(triplet.get_potential_energy() - singlet.get_potential_energy())

-0.5508372783660889

Example of adsorbate relaxation - OC20#

Here we just setup a Cu(100) slab with a CO on it and relax it.

This is an OC20 task because it is a slab with an adsorbate.

We specify an explicit device in the predictor here, and avoid the warning.

from ase.build import add_adsorbate, fcc100, molecule

from ase.optimize import LBFGS

from fairchem.core import FAIRChemCalculator, pretrained_mlip

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1")

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="oc20")

# Set up your system as an ASE atoms object

slab = fcc100("Cu", (3, 3, 3), vacuum=8, periodic=True)

adsorbate = molecule("CO")

add_adsorbate(slab, adsorbate, 2.0, "bridge")

slab.calc = calc

# Set up LBFGS dynamics object

opt = LBFGS(slab)

opt.run(0.05, 100)

print(slab.get_potential_energy())

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

Step Time Energy fmax

LBFGS: 0 21:52:21 -89.596203 11.451670

LBFGS: 1 21:52:22 -92.497568 6.543859

LBFGS: 2 21:52:22 -92.624428 7.536283

LBFGS: 3 21:52:22 -93.000906 3.715973

LBFGS: 4 21:52:22 -93.158687 3.479858

LBFGS: 5 21:52:22 -93.264149 2.256852

LBFGS: 6 21:52:22 -93.505251 1.133162

LBFGS: 7 21:52:22 -93.595938 0.991849

LBFGS: 8 21:52:22 -93.705356 0.683693

LBFGS: 9 21:52:22 -93.791545 0.506521

LBFGS: 10 21:52:22 -93.837927 0.364016

LBFGS: 11 21:52:22 -93.856805 0.349534

LBFGS: 12 21:52:22 -93.881769 0.498560

LBFGS: 13 21:52:23 -93.900197 0.432910

LBFGS: 14 21:52:23 -93.910015 0.156405

LBFGS: 15 21:52:23 -93.915885 0.170004

LBFGS: 16 21:52:23 -93.922146 0.211723

LBFGS: 17 21:52:23 -93.929011 0.260897

LBFGS: 18 21:52:23 -93.935161 0.183900

LBFGS: 19 21:52:23 -93.938071 0.057366

LBFGS: 20 21:52:23 -93.938498 0.039144

-93.9384984000145

Example bulk relaxation - OMAT#

from ase.build import bulk

from ase.filters import FrechetCellFilter

from ase.optimize import FIRE

from fairchem.core import FAIRChemCalculator, pretrained_mlip

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1")

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omat")

atoms = bulk("Fe")

atoms.calc = calc

opt = FIRE(FrechetCellFilter(atoms))

opt.run(0.05, 100)

print(atoms.get_stress()) # !!!! We get stress now!

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

Step Time Energy fmax

FIRE: 0 21:52:25 -8.261158 0.651784

FIRE: 1 21:52:26 -8.271310 0.358119

FIRE: 2 21:52:26 -8.264588 1.650196

FIRE: 3 21:52:26 -8.273672 0.177966

FIRE: 4 21:52:26 -8.272634 0.269087

FIRE: 5 21:52:26 -8.272766 0.257552

FIRE: 6 21:52:26 -8.273009 0.234351

FIRE: 7 21:52:26 -8.273319 0.199206

FIRE: 8 21:52:26 -8.273635 0.151744

FIRE: 9 21:52:26 -8.273890 0.091454

FIRE: 10 21:52:26 -8.274015 0.017801

[1.5562563e-03 1.5562196e-03 1.5562959e-03 3.4555761e-08 3.1117042e-09

3.7002938e-08]

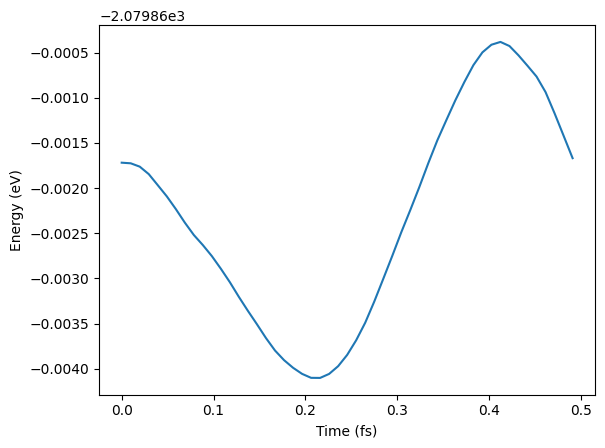

Molecular dynamics - OMOL#

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from ase import units

from ase.build import molecule

from ase.io import Trajectory

from ase.md.langevin import Langevin

from fairchem.core import FAIRChemCalculator, pretrained_mlip

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1")

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omol")

atoms = molecule("H2O")

atoms.info.update(charge=0, spin=1) # For omol

atoms.calc = calc

dyn = Langevin(

atoms,

timestep=0.1 * units.fs,

temperature_K=400,

friction=0.001 / units.fs,

)

trajectory = Trajectory("my_md.traj", "w", atoms)

dyn.attach(trajectory.write, interval=1)

dyn.run(steps=50)

# See some results - not paper ready!

traj = Trajectory("my_md.traj")

plt.plot(

[i * 0.1 * units.fs for i in range(len(traj))],

[a.get_potential_energy() for a in traj],

)

plt.xlabel("Time (fs)")

plt.ylabel("Energy (eV)");

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

Catalyst Adsorption energies#

The basic approach in computing an adsorption energy is to compute this energy difference:

dH = E_adslab - E_slab - E_ads

We use UMA for two of these energies E_adslab and E_slab. For E_ads We have to do something a little different. The OC20 task is not trained for molecules or molecular fragments. We use atomic energy reference energies instead. These are tabulated below.

The OC20 reference scheme is this reaction:

x CO + (x + y/2 - z) H2 + (z-x) H2O + w/2 N2 + * -> CxHyOzNw*

For this example we have

-H2 + H2O + * -> O*. "O": -7.204 eV

Where "O": -7.204 is a constant.

To get the desired reaction energy we want we add the formation energy of water. We use either DFT or experimental values for this reaction energy.

1/2O2 + H2 -> H2O

Alternatives to this approach are using DFT to estimate the energy of 1/2 O2, just make sure to use consistent settings with your task. You should not use OMOL for this.

from ase.build import add_adsorbate, fcc111

from ase.optimize import BFGS

from fairchem.core import FAIRChemCalculator, pretrained_mlip

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1")

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="oc20")

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

# reference energies from a linear combination of H2O/N2/CO/H2!

atomic_reference_energies = {

"H": -3.477,

"N": -8.083,

"O": -7.204,

"C": -7.282,

}

re1 = -3.03 # Water formation energy from experiment

slab = fcc111("Pt", size=(2, 2, 5), vacuum=20.0)

slab.pbc = True

adslab = slab.copy()

add_adsorbate(adslab, "O", height=1.2, position="fcc")

slab.calc = calc

opt = BFGS(slab)

print("Relaxing slab")

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=100)

slab_e = slab.get_potential_energy()

adslab.calc = calc

opt = BFGS(adslab)

print("\nRelaxing adslab")

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=100)

adslab_e = adslab.get_potential_energy()

Relaxing slab

Step Time Energy fmax

BFGS: 0 21:52:35 -104.710392 0.707696

BFGS: 1 21:52:35 -104.767890 0.605448

BFGS: 2 21:52:35 -104.919425 0.369265

BFGS: 3 21:52:35 -104.952877 0.441349

BFGS: 4 21:52:35 -105.030000 0.467592

BFGS: 5 21:52:35 -105.091451 0.365231

BFGS: 6 21:52:35 -105.128721 0.195037

BFGS: 7 21:52:36 -105.143315 0.048836

Relaxing adslab

Step Time Energy fmax

BFGS: 0 21:52:36 -110.055657 1.762239

BFGS: 1 21:52:36 -110.239039 0.996808

BFGS: 2 21:52:36 -110.389562 0.747533

BFGS: 3 21:52:36 -110.441196 0.818361

BFGS: 4 21:52:36 -110.557367 0.688425

BFGS: 5 21:52:36 -110.631217 0.497350

BFGS: 6 21:52:36 -110.687290 0.690799

BFGS: 7 21:52:36 -110.737889 0.729393

BFGS: 8 21:52:36 -110.774873 0.435709

BFGS: 9 21:52:36 -110.786666 0.199874

BFGS: 10 21:52:36 -110.789560 0.080701

BFGS: 11 21:52:36 -110.790040 0.057997

BFGS: 12 21:52:37 -110.790287 0.044009

Now we compute the adsorption energy.

# Energy for ((H2O-H2) + * -> *O) + (H2 + 1/2O2 -> H2O) leads to 1/2O2 + * -> *O!

adslab_e - slab_e - atomic_reference_energies["O"] + re1

-1.4729712207147325

How did we do? We need a reference point. In the paper below, there is an atomic adsorption energy for O on Pt(111) of about -4.264 eV. This is for the reaction O + * -> O*. To convert this to the dissociative adsorption energy, we have to add the reaction:

1/2 O2 -> O D = 2.58 eV (expt)

to get a comparable energy of about -1.68 eV. There is about ~0.2 eV difference (we predicted -1.47 eV above, and the reference comparison is -1.68 eV) to account for. The biggest difference is likely due to the differences in exchange-correlation functional. The reference data used the PBE functional, and eSCN was trained on RPBE data. To additional places where there are differences include:

Difference in lattice constant

The reference energy used for the experiment references. These can differ by up to 0.5 eV from comparable DFT calculations.

How many layers are relaxed in the calculation

Some of these differences tend to be systematic, and you can calibrate and correct these, especially if you can augment these with your own DFT calculations.

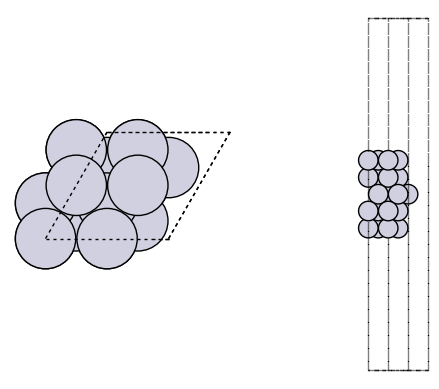

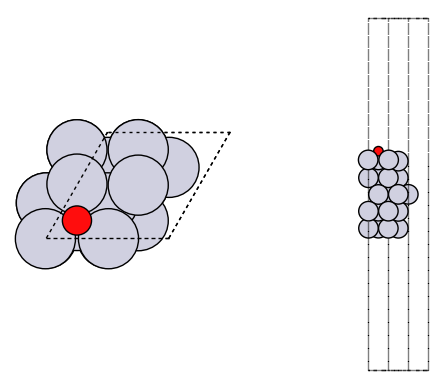

It is always a good idea to visualize the geometries to make sure they look reasonable.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from ase.visualize.plot import plot_atoms

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 2)

plot_atoms(slab, axs[0])

plot_atoms(slab, axs[1], rotation=("-90x"))

axs[0].set_axis_off()

axs[1].set_axis_off()

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 2)

plot_atoms(adslab, axs[0])

plot_atoms(adslab, axs[1], rotation=("-90x"))

axs[0].set_axis_off()

axs[1].set_axis_off()

Molecular vibrations#

from ase import Atoms

from ase.optimize import BFGS

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1")

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omol")

from ase.vibrations import Vibrations

n2 = Atoms("N2", [(0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 1.1)])

n2.info.update({"spin": 1, "charge": 0})

n2.calc = calc

BFGS(n2).run(fmax=0.01)

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

Step Time Energy fmax

BFGS: 0 21:52:41 -2981.068009 1.645285

BFGS: 1 21:52:41 -2980.961841 6.601501

BFGS: 2 21:52:41 -2981.076753 0.203644

BFGS: 3 21:52:41 -2981.076882 0.024169

BFGS: 4 21:52:41 -2981.076883 0.000104

np.True_

vib = Vibrations(n2)

vib.run()

vib.summary()

---------------------

# meV cm^-1

---------------------

0 0.0i 0.0i

1 0.0i 0.0i

2 0.0 0.0

3 2.0 16.1

4 2.0 16.1

5 309.2 2494.2

---------------------

Zero-point energy: 0.157 eV

Bulk alloy phase behavior#

Adapted from https://kitchingroup.cheme.cmu.edu/dft-book/dft.html#orgheadline29

We manually compute the formation energy of pure compounds and some alloy compositions to assess stability.

from ase.atoms import Atom, Atoms

from ase.filters import FrechetCellFilter

from ase.optimize import FIRE

from fairchem.core import FAIRChemCalculator, pretrained_mlip

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1")

cu = Atoms(

[Atom("Cu", [0.000, 0.000, 0.000])],

cell=[[1.818, 0.000, 1.818], [1.818, 1.818, 0.000], [0.000, 1.818, 1.818]],

pbc=True,

)

cu.calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omat")

opt = FIRE(FrechetCellFilter(cu))

opt.run(0.05, 100)

cu.get_potential_energy()

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

Step Time Energy fmax

FIRE: 0 21:52:44 -3.756933 0.161999

FIRE: 1 21:52:44 -3.757594 0.110083

FIRE: 2 21:52:44 -3.758130 0.020766

-3.7581302754134702

pd = Atoms(

[Atom("Pd", [0.000, 0.000, 0.000])],

cell=[[1.978, 0.000, 1.978], [1.978, 1.978, 0.000], [0.000, 1.978, 1.978]],

pbc=True,

)

pd.calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omat")

opt = FIRE(FrechetCellFilter(pd))

opt.run(0.05, 100)

pd.get_potential_energy()

Step Time Energy fmax

FIRE: 0 21:52:45 -5.211726 0.240058

FIRE: 1 21:52:45 -5.213070 0.131577

FIRE: 2 21:52:45 -5.213503 0.060260

FIRE: 3 21:52:45 -5.213528 0.051645

FIRE: 4 21:52:45 -5.213565 0.035871

-5.213564711544393

Alloy formation energies#

cupd1 = Atoms(

[Atom("Cu", [0.000, 0.000, 0.000]), Atom("Pd", [-1.652, 0.000, 2.039])],

cell=[[0.000, -2.039, 2.039], [0.000, 2.039, 2.039], [-3.303, 0.000, 0.000]],

pbc=True,

) # Note pbc=True is important, it is not the default and OMAT

cupd1.calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omat")

opt = FIRE(FrechetCellFilter(cupd1))

opt.run(0.05, 100)

cupd1.get_potential_energy()

Step Time Energy fmax

FIRE: 0 21:52:45 -9.202820 0.142029

FIRE: 1 21:52:45 -9.203042 0.127498

FIRE: 2 21:52:45 -9.203371 0.101174

FIRE: 3 21:52:45 -9.203669 0.068563

FIRE: 4 21:52:45 -9.203892 0.060712

FIRE: 5 21:52:45 -9.204129 0.078850

FIRE: 6 21:52:46 -9.204490 0.081599

FIRE: 7 21:52:46 -9.204987 0.069264

FIRE: 8 21:52:46 -9.205592 0.045645

-9.205591734189348

cupd2 = Atoms(

[

Atom("Cu", [-0.049, 0.049, 0.049]),

Atom("Cu", [-11.170, 11.170, 11.170]),

Atom("Pd", [-7.415, 7.415, 7.415]),

Atom("Pd", [-3.804, 3.804, 3.804]),

],

cell=[[-5.629, 3.701, 5.629], [-3.701, 5.629, 5.629], [-5.629, 5.629, 3.701]],

pbc=True,

)

cupd2.calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omat")

opt = FIRE(FrechetCellFilter(cupd2))

opt.run(0.05, 100)

cupd2.get_potential_energy()

Step Time Energy fmax

FIRE: 0 21:52:46 -18.126594 0.181633

FIRE: 1 21:52:46 -18.127546 0.162952

FIRE: 2 21:52:46 -18.129065 0.127294

FIRE: 3 21:52:46 -18.130533 0.078068

FIRE: 4 21:52:46 -18.131347 0.021487

-18.13134681371561

# Delta Hf cupd-1 = -0.11 eV/atom

hf1 = (

cupd1.get_potential_energy() - cu.get_potential_energy() - pd.get_potential_energy()

)

hf1

-0.23389674723148435

# DFT: Delta Hf cupd-2 = -0.04 eV/atom

hf2 = (

cupd2.get_potential_energy()

- 2 * cu.get_potential_energy()

- 2 * pd.get_potential_energy()

)

hf2

-0.18795683979988276

hf1 - hf2, (-0.11 - -0.04)

(-0.04593990743160159, -0.07)

These indicate that cupd-1 and cupd-2 are both more stable than phase separated Cu and Pd, and that cupd-1 is more stable than cupd-2. The absolute formation energies differ from the DFT references, but the relative differences are quite close. The absolute differences could be due to DFT parameter choices (XC, psp, etc.).

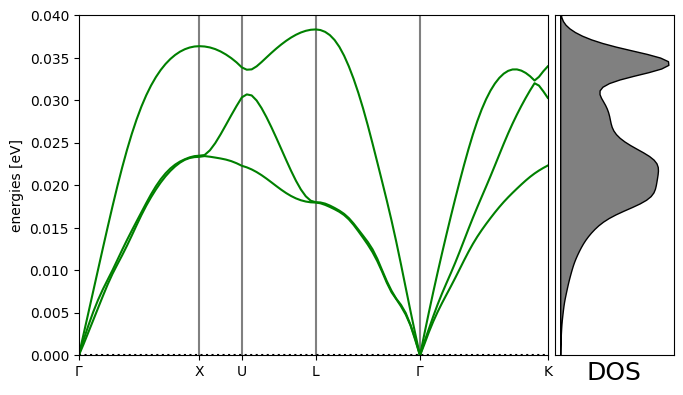

Phonon calculation#

This takes 4-10 minutes. Adapted from https://wiki.fysik.dtu.dk/ase/ase/phonons.html#example.

Phonons have applications in computing the stability and free energy of solids. See:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359646215003127

https://iopscience.iop.org/book/mono/978-0-7503-2572-1/chapter/bk978-0-7503-2572-1ch1

from ase.build import bulk

from ase.phonons import Phonons

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1")

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omat")

# Setup crystal

atoms = bulk("Al", "fcc", a=4.05)

# Phonon calculator

N = 7

ph = Phonons(atoms, calc, supercell=(N, N, N), delta=0.05)

ph.run()

# Read forces and assemble the dynamical matrix

ph.read(acoustic=True)

ph.clean()

path = atoms.cell.bandpath("GXULGK", npoints=100)

bs = ph.get_band_structure(path)

dos = ph.get_dos(kpts=(20, 20, 20)).sample_grid(npts=100, width=1e-3)

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

WARNING, 1 imaginary frequencies at q = ( 0.00, 0.00, 0.00) ; (omega_q = 7.041e-09*i)

WARNING, 1 imaginary frequencies at q = ( 0.00, 0.00, 0.00) ; (omega_q = 7.041e-09*i)

# Plot the band structure and DOS:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # noqa

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(7, 4))

ax = fig.add_axes([0.12, 0.07, 0.67, 0.85])

emax = 0.04

bs.plot(ax=ax, emin=0.0, emax=emax)

dosax = fig.add_axes([0.8, 0.07, 0.17, 0.85])

dosax.fill_between(

dos.get_weights(),

dos.get_energies(),

y2=0,

color="grey",

edgecolor="k",

lw=1,

)

dosax.set_ylim(0, emax)

dosax.set_yticks([])

dosax.set_xticks([])

dosax.set_xlabel("DOS", fontsize=18);

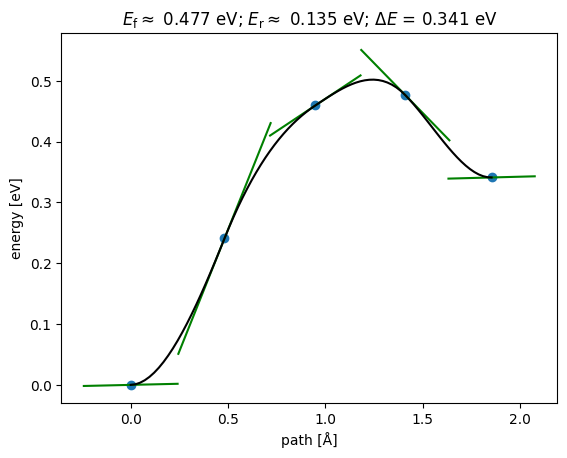

Transition States (NEBs)#

Nudged elastic band calculations are among the most costly calculations we do. UMA makes these quicker!

Get initial state

Get final state

Construct band and interpolate the images

Relax the band

Analyze and plot the band.

We explore diffusion of an O adatom from an hcp to an fcc site on Pt(111).

Initial state#

from ase.build import add_adsorbate, fcc111, molecule

from ase.optimize import LBFGS

from fairchem.core import FAIRChemCalculator, pretrained_mlip

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1")

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="oc20")

# Set up your system as an ASE atoms object

initial = fcc111("Pt", (3, 3, 3), vacuum=8, periodic=True)

adsorbate = molecule("O")

add_adsorbate(initial, adsorbate, 2.0, "fcc")

initial.calc = calc

# Set up LBFGS dynamics object

opt = LBFGS(initial)

opt.run(0.05, 100)

print(initial.get_potential_energy())

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

Step Time Energy fmax

LBFGS: 0 21:52:56 -141.329801 3.509944

LBFGS: 1 21:52:56 -141.719928 3.515034

LBFGS: 2 21:52:56 -142.980943 2.978368

LBFGS: 3 21:52:56 -143.684058 0.968200

LBFGS: 4 21:52:56 -143.787056 1.271672

LBFGS: 5 21:52:56 -143.858780 0.874625

LBFGS: 6 21:52:56 -143.933924 0.170912

LBFGS: 7 21:52:56 -143.937118 0.152462

LBFGS: 8 21:52:56 -143.944597 0.122234

LBFGS: 9 21:52:56 -143.948826 0.109289

LBFGS: 10 21:52:57 -143.952234 0.069971

LBFGS: 11 21:52:57 -143.953716 0.080111

LBFGS: 12 21:52:57 -143.955176 0.083489

LBFGS: 13 21:52:57 -143.956801 0.066262

LBFGS: 14 21:52:57 -143.958312 0.031495

-143.9583123027719

Final state#

# Set up your system as an ASE atoms object

final = fcc111("Pt", (3, 3, 3), vacuum=8, periodic=True)

adsorbate = molecule("O")

add_adsorbate(final, adsorbate, 2.0, "hcp")

final.calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="oc20")

# Set up LBFGS dynamics object

opt = LBFGS(final)

opt.run(0.05, 100)

print(final.get_potential_energy())

Step Time Energy fmax

LBFGS: 0 21:52:57 -141.282604 3.340431

LBFGS: 1 21:52:57 -141.659793 3.323328

LBFGS: 2 21:52:57 -142.891404 2.596618

LBFGS: 3 21:52:57 -143.418901 1.225930

LBFGS: 4 21:52:57 -143.484096 0.977174

LBFGS: 5 21:52:57 -143.606344 0.136708

LBFGS: 6 21:52:57 -143.610842 0.118672

LBFGS: 7 21:52:58 -143.613319 0.100140

LBFGS: 8 21:52:58 -143.615008 0.078482

LBFGS: 9 21:52:58 -143.616454 0.051593

LBFGS: 10 21:52:58 -143.617140 0.033146

-143.61714008444915

Setup and relax the band#

from ase.mep import NEB

images = [initial]

for i in range(3):

image = initial.copy()

image.calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="oc20")

images.append(image)

images.append(final)

neb = NEB(images)

neb.interpolate()

opt = LBFGS(neb, trajectory="neb.traj")

opt.run(0.05, 100)

Step Time Energy fmax

LBFGS: 0 21:52:58 -143.193978 3.039289

LBFGS: 1 21:52:58 -143.360196 1.460894

LBFGS: 2 21:52:59 -143.411349 0.450309

LBFGS: 3 21:52:59 -143.423401 0.447560

LBFGS: 4 21:52:59 -143.443052 0.476377

LBFGS: 5 21:52:59 -143.459314 0.378516

LBFGS: 6 21:53:00 -143.469905 0.211698

LBFGS: 7 21:53:00 -143.474784 0.177269

LBFGS: 8 21:53:00 -143.475807 0.183701

LBFGS: 9 21:53:00 -143.477287 0.178498

LBFGS: 10 21:53:01 -143.478790 0.167185

LBFGS: 11 21:53:01 -143.479388 0.094902

LBFGS: 12 21:53:01 -143.479540 0.096952

LBFGS: 13 21:53:01 -143.479789 0.100267

LBFGS: 14 21:53:02 -143.480348 0.124768

LBFGS: 15 21:53:02 -143.481008 0.092785

LBFGS: 16 21:53:02 -143.481432 0.050531

LBFGS: 17 21:53:02 -143.481732 0.040594

np.True_

from ase.mep import NEBTools

NEBTools(neb.images).plot_band();

This could be a good initial guess to initialize an NEB in DFT.

Ideas for things you can do with UMA#

FineTuna - use it for initial geometry optimizations then do DFT

a. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2632-2153/ac8fe0

b. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2632-2153/ad37f0

AdsorbML - prescreen adsorption sites to find relevant ones

a. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41524-023-01121-5

CatTsunami - screen NEBs more thoroughly

a. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.4c04272

Free energy estimations - compute vibrational modes and use them to estimate vibrational entropy

a. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcc.4c07477

Massive screening of catalyst surface properties (685M relaxations)

a. https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.11783

Advanced applications#

These take a while to run.

AdsorbML#

It is so cheap to run these calculations that we can screen a broad range of adsorbate sites and rank them in stability. The AdsorbML approach automates this. This takes quite a while to run here, and we don’t do it in the workshop.

Expert adsorption energies#

This tutorial reproduces Fig 6b from the following paper: Zhou, Jing, et al. “Enhanced Catalytic Activity of Bimetallic Ordered Catalysts for Nitrogen Reduction Reaction by Perturbation of Scaling Relations.” ACS Catalysis 134 (2023): 2190-2201 (https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.2c05877).

This takes up to an hour with a GPU, and much longer with a CPU.

CatTsunami#

The CatTsunami tutorial is an example of enumerating initial and final states, and computing reaction paths between them with UMA.

Acknowledgements#

This tutorial was originally compiled by John Kitchin (CMU) for the NAM29 catalysis tutorial session, using a variety of resources from the FAIR chemistry repository.