UMA Catalysis Tutorial#

Author: Zack Ulissi (Meta, CMU), with help from AI coding agents / LLMs

Original paper: Bjarne Kreitz et al. JPCC (2021)

Overview#

This tutorial demonstrates how to use the Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) machine learning potential to perform comprehensive catalyst surface analysis. We replicate key computational workflows from “Microkinetic Modeling of CO₂ Desorption from Supported Multifaceted Ni Catalysts” by Bjarne Kreitz (now faculty at Georgia Tech!), showing how ML potentials can accelerate computational catalysis research.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this tutorial, you will be able to:

Optimize bulk crystal structures and extract lattice constants

Calculate surface energies using linear extrapolation methods

Construct Wulff shapes to predict nanoparticle morphologies

Compute adsorption energies with zero-point energy corrections

Study coverage-dependent binding phenomena

Calculate reaction barriers using the nudged elastic band (NEB) method

Apply D3 dispersion corrections to improve accuracy

About UMA-S-1P1

The UMA-S-1P1 model is a state-of-the-art universal machine learning potential trained on the OMat24, OC20, OMol25, ODAC23, and OMC25 datasets, covering diverse materials and surface chemistries. It provides ~1000× speedup over DFT while maintaining reasonable accuracy for screening studies. Here we’ll use the UMA-s-1p1 checkpoint which is the small (=faster) 1.1 version released in June. The UMA-s-1p1 checkpoint is open science with a lightweight license that users have to agree to through Huggingface.

You can read more about the UMA models here: https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.23971

Installation and Setup#

This tutorial uses a number of helpful open source packages:

ase- Atomic Simulation Environmentfairchem- FAIR Chemistry ML potentials (formerly OCP)pymatgen- Materials analysismatplotlib- Visualizationnumpy- Numerical computingtorch-dftd- Dispersion corrections among many others!

Huggingface setups#

You need to get a HuggingFace account and request access to the UMA models.

You need a Huggingface account, request access to https://huggingface.co/facebook/UMA, and to create a Huggingface token at https://huggingface.co/settings/tokens/ with these permission:

Permissions: Read access to contents of all public gated repos you can access

Then, add the token as an environment variable using huggingface-cli login:

# Enter token via huggingface-cli

! huggingface-cli login

or you can set the token via HF_TOKEN variable:

# Set token via env variable

import os

os.environ["HF_TOKEN"] = "MYTOKEN"

FAIR Chemistry (UMA) installation#

It may be enough to use pip install fairchem-core. This gets you the latest version on PyPi (https://pypi.org/project/fairchem-core/)

Here we install some sub-packages. This can take 2-5 minutes to run.

! pip install fairchem-core[docs] fairchem-data-oc fairchem-applications-cattsunami x3dase

# Check that packages are installed

!pip list | grep fairchem

fairchem-applications-cattsunami 1.1.2.dev135+g1de48c96

fairchem-core 2.13.1.dev13+g1de48c96

fairchem-data-oc 1.0.3.dev135+g1de48c96

fairchem-data-omat 0.2.1.dev40+g1de48c96

import fairchem.core

fairchem.core.__version__

'2.13.1.dev13+g1de48c96'

Package imports#

First, let’s import all necessary libraries and initialize the UMA-S-1P1 predictor:

from pathlib import Path

import ase.io

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from ase import Atoms

from ase.build import bulk

from ase.constraints import FixBondLengths

from ase.io import write

from ase.mep import interpolate

from ase.mep.dyneb import DyNEB

from ase.optimize import FIRE, LBFGS

from ase.vibrations import Vibrations

from ase.visualize import view

from fairchem.core import FAIRChemCalculator, pretrained_mlip

from fairchem.data.oc.core import (

Adsorbate,

AdsorbateSlabConfig,

Bulk,

MultipleAdsorbateSlabConfig,

Slab,

)

from pymatgen.analysis.wulff import WulffShape

from pymatgen.core import Lattice, Structure

from pymatgen.core.surface import SlabGenerator

from pymatgen.io.ase import AseAtomsAdaptor

from torch_dftd.torch_dftd3_calculator import TorchDFTD3Calculator

# Set up output directory structure

output_dir = Path("ni_tutorial_results")

output_dir.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

# Create subdirectories for each part

part_dirs = {

"part1": "part1-bulk-optimization",

"part2": "part2-surface-energies",

"part3": "part3-wulff-construction",

"part4": "part4-h-adsorption",

"part5": "part5-coverage-dependence",

"part6": "part6-co-dissociation",

}

for key, dirname in part_dirs.items():

(output_dir / dirname).mkdir(exist_ok=True)

# Create subdirectories for different facets in part2

for facet in ["111", "100", "110", "211"]:

(output_dir / part_dirs["part2"] / f"ni{facet}").mkdir(exist_ok=True)

# Initialize the UMA-S-1P1 predictor

print("\nLoading UMA-S-1P1 model...")

predictor = pretrained_mlip.get_predict_unit("uma-s-1p1")

print("✓ Model loaded successfully!")

Loading UMA-S-1P1 model...

WARNING:root:device was not explicitly set, using device='cuda'.

✓ Model loaded successfully!

It is somewhat time consuming to run this. We’re going to use a small number of bulks for the testing of this documentation, but otherwise run all of the results for the actual documentation.

import os

fast_docs = os.environ.get("FAST_DOCS", "false").lower() == "true"

if fast_docs:

num_sites = 2

relaxation_steps = 20

else:

num_sites = 5

relaxation_steps = 300

Part 1: Bulk Crystal Optimization#

Introduction#

Before studying surfaces, we need to determine the equilibrium lattice constant of bulk Ni. This is crucial because surface energies and adsorbate binding depend strongly on the underlying lattice parameter.

Theory#

For FCC metals like Ni, the lattice constant a defines the unit cell size. The experimental value for Ni is a = 3.524 Å at room temperature. We’ll optimize both atomic positions and the cell volume to find the ML potential’s equilibrium structure.

# Create initial FCC Ni structure

a_initial = 3.52 # Å, close to experimental

ni_bulk = bulk("Ni", "fcc", a=a_initial, cubic=True)

print(f"Initial lattice constant: {a_initial:.2f} Å")

print(f"Number of atoms: {len(ni_bulk)}")

# Set up calculator for bulk optimization

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omat")

ni_bulk.calc = calc

# Use ExpCellFilter to allow cell relaxation

from ase.filters import ExpCellFilter

ecf = ExpCellFilter(ni_bulk)

# Optimize with LBFGS

opt = LBFGS(

ecf,

trajectory=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part1"] / "ni_bulk_opt.traj"),

logfile=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part1"] / "ni_bulk_opt.log"),

)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

# Extract results

cell = ni_bulk.get_cell()

a_optimized = cell[0, 0]

a_exp = 3.524 # Experimental value

error = abs(a_optimized - a_exp) / a_exp * 100

print(f"\n{'='*50}")

print(f"Experimental lattice constant: {a_exp:.2f} Å")

print(f"Optimized lattice constant: {a_optimized:.2f} Å")

print(f"Relative error: {error:.2f}%")

print(f"{'='*50}")

ase.io.write(str(output_dir / part_dirs["part1"] / "ni_bulk_relaxed.cif"), ni_bulk)

# Store results for later use

a_opt = a_optimized

Initial lattice constant: 3.52 Å

Number of atoms: 4

/tmp/ipykernel_8078/3959847705.py:15: DeprecationWarning: Use FrechetCellFilter for better convergence w.r.t. cell variables.

ecf = ExpCellFilter(ni_bulk)

==================================================

Experimental lattice constant: 3.52 Å

Optimized lattice constant: 3.52 Å

Relative error: 0.25%

==================================================

Missing UMA access?

Don’t have access to UMA yet? You can still explore this calculation!

Download example Ni bulk structure and test it in the UMA demo (no login required) to see how the model predicts properties for bulk Ni.

Understanding the Results

UMA-s-1p1 using the omat task name will predict lattice constants at the PBE level of DFT. For metals, PBE typically predicts lattice constants within 1-2% of experimental values.

Small discrepancies arise from:

Training data biases (if your structure is far from OMAT24)

Temperature effects (0 K vs room temperature). You can do a quasi-harmonic analysis to include finite temperature effects if desired.

Quantum effects not captured by the underlying DFT/PBE simulations

For surface calculations, using the ML-optimized lattice constant maintains internal consistency.

Comparison with Paper

Paper (Table 1): Ni lattice constant = 3.524 Å (experimental reference)

The UMA-S-1P1 model with OMAT provides excellent agreement with experiment, as would be expected for the PBE functional for simple BCC Ni. The underlying calculations for OMat24 and the original results cited in the paper should be very similar (both PBE), so the fact that the results are a little closer to experiment than the original results is within the numerical noise of the ML model.

Further exploration

Try modifying the following parameters and observe the effects:

Task name: The original paper re-relaxed the structures at the RPBE level of theory before continuing. Try that with the UMA-s-1p1 model (using the oc20 task name) and see if it matters here.

Initial guess: Change

a_initialto 3.0 or 4.0 Å. Does the optimizer still converge to the same value?Convergence criterion: Tighten

fmaxto 0.01 eV/Å. How many more steps are required?Different metals: Replace

"Ni"with"Cu","Pd", or"Pt". Compare predicted vs experimental lattice constants.Cell shape: Remove

cubic=Trueand allow the cell to distort. Does FCC remain stable?

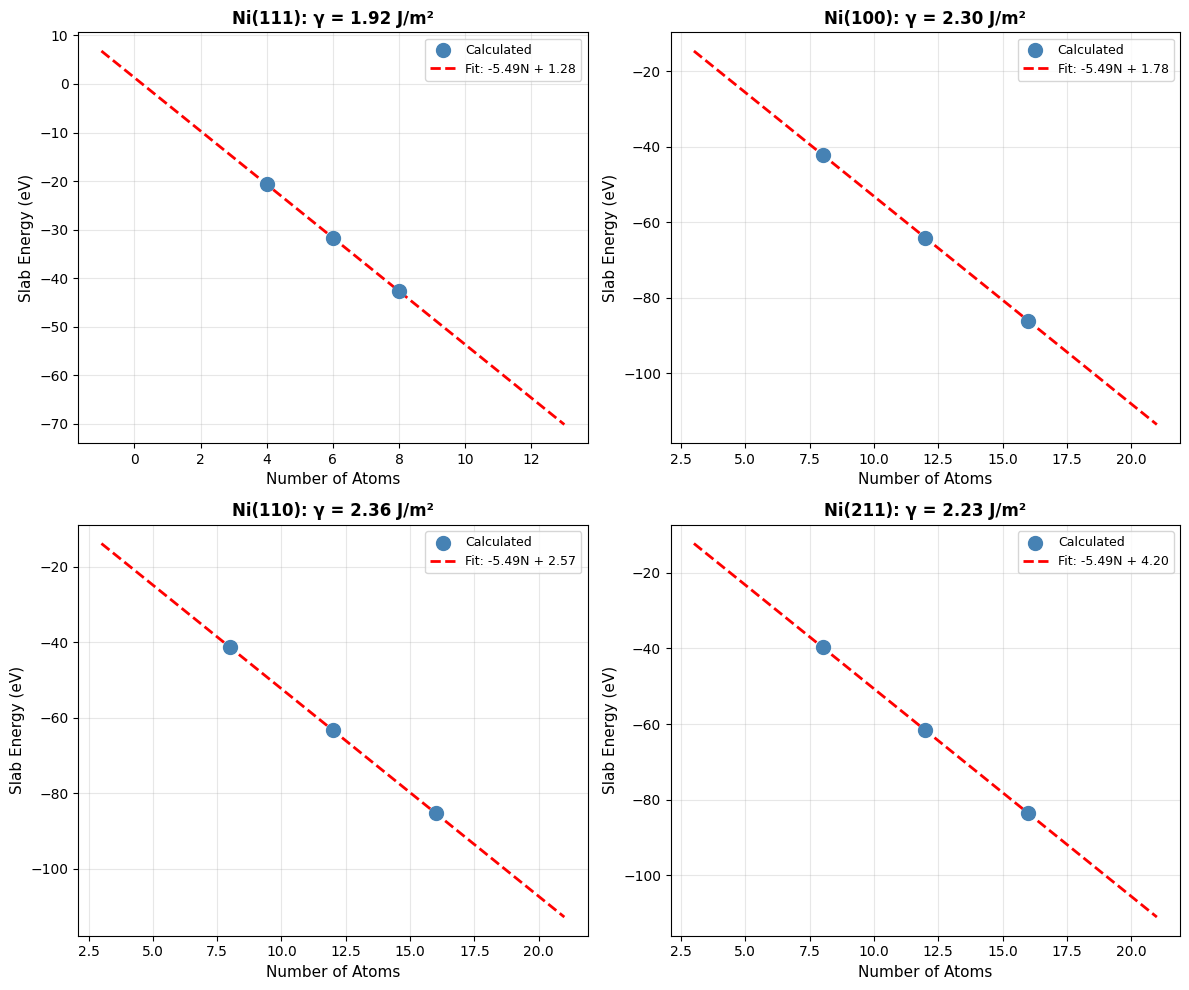

Part 2: Surface Energy Calculations#

Introduction#

Surface energy (γ) quantifies the thermodynamic cost of creating a surface. It determines surface stability, morphology, and catalytic activity. We’ll calculate γ for four low-index Ni facets: (111), (100), (110), and (211).

Theory#

The surface energy is defined as:

where:

\(E_{\text{slab}}\) = total energy of the slab

\(N\) = number of atoms in the slab

\(E_{\text{bulk}}\) = bulk energy per atom

\(A\) = surface area

Factor of 2 accounts for two surfaces (top and bottom)

Challenge: Direct calculation suffers from quantum size effects, and if you were doing DFT calculations small numerical errors in the simulation or from the K-point grid sampling can lead to small (but significant) errors in the bulk lattice energy.

Solution: It is fairly common when calculating surface energies to use the bulk energy from a bulk relaxation in the above equation. However, because DFT often has some small numerical noise in the predictions from k-point convergence, this might lead to the wrong surface energy. Instead, two more careful schemes are either:

Calculate the energy of a bulk structure oriented to each slab to maximize cancellation of small numerical errors or

Calculate the energy of multiple slabs at multiple thicknesses and extrapolate to zero thickness. The intercept will be the surface energy, and the slope will be a fitted bulk energy. A benefit of this approach is that it also forces us to check that we have a sufficiently thick slab for a well defined surface energy; if the fit is non-linear we need thicker slabs.

We’ll use the linear extrapolation method here as it’s more likely to work in future DFT studies if you use this code!

Step 1: Setup and Bulk Energy Reference#

First, we’ll set up the calculation parameters and get the bulk energy reference:

# Calculate surface energies for all facets

facets = [(1, 1, 1), (1, 0, 0), (1, 1, 0), (2, 1, 1)]

surface_energies = {}

surface_energies_SI = {}

all_fit_data = {}

# Get bulk energy reference (only need to do this once)

E_bulk_total = ni_bulk.get_potential_energy()

N_bulk = len(ni_bulk)

E_bulk_per_atom = E_bulk_total / N_bulk

print(f"Bulk energy reference:")

print(f" Total energy: {E_bulk_total:.2f} eV")

print(f" Number of atoms: {N_bulk}")

print(f" Energy per atom: {E_bulk_per_atom:.6f} eV/atom")

Bulk energy reference:

Total energy: -21.97 eV

Number of atoms: 4

Energy per atom: -5.491441 eV/atom

Step 2: Generate and Relax Slabs#

Now we’ll loop through each facet, generating slabs at three different thicknesses:

# Convert bulk to pymatgen structure for slab generation

adaptor = AseAtomsAdaptor()

ni_structure = adaptor.get_structure(ni_bulk)

for facet in facets:

facet_str = "".join(map(str, facet))

print(f"\n{'='*60}")

print(f"Calculating Ni({facet_str}) surface energy")

print(f"{'='*60}")

# Calculate for three thicknesses

thicknesses = [4, 6, 8] # layers

n_atoms_list = []

energies_list = []

for n_layers in thicknesses:

print(f"\n Thickness: {n_layers} layers")

# Generate slab

slabgen = SlabGenerator(

ni_structure,

facet,

min_slab_size=n_layers * a_opt / np.sqrt(sum([h**2 for h in facet])),

min_vacuum_size=10.0,

center_slab=True,

)

pmg_slab = slabgen.get_slabs()[0]

slab = adaptor.get_atoms(pmg_slab)

slab.center(vacuum=10.0, axis=2)

print(f" Atoms: {len(slab)}")

# Relax slab (no constraints - both surfaces free)

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="omat")

slab.calc = calc

opt = LBFGS(slab, logfile=None)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_slab = slab.get_potential_energy()

n_atoms_list.append(len(slab))

energies_list.append(E_slab)

print(f" Energy: {E_slab:.2f} eV")

# Linear regression: E_slab = slope * N + intercept

coeffs = np.polyfit(n_atoms_list, energies_list, 1)

slope = coeffs[0]

intercept = coeffs[1]

# Extract surface energy from intercept

cell = slab.get_cell()

area = np.linalg.norm(np.cross(cell[0], cell[1]))

gamma = intercept / (2 * area) # eV/Ų

gamma_SI = gamma * 16.0218 # J/m²

print(f"\n Linear fit:")

print(f" Slope: {slope:.6f} eV/atom (cf. bulk {E_bulk_per_atom:.6f})")

print(f" Intercept: {intercept:.2f} eV")

print(f"\n Surface energy:")

print(f" γ = {gamma:.6f} eV/Ų = {gamma_SI:.2f} J/m²")

# Store results and fit data

surface_energies[facet] = gamma

surface_energies_SI[facet] = gamma_SI

all_fit_data[facet] = {

"n_atoms": n_atoms_list,

"energies": energies_list,

"slope": slope,

"intercept": intercept,

}

============================================================

Calculating Ni(111) surface energy

============================================================

Thickness: 4 layers

Atoms: 4

Energy: -20.69 eV

Thickness: 6 layers

Atoms: 6

Energy: -31.67 eV

Thickness: 8 layers

Atoms: 8

Energy: -42.66 eV

Linear fit:

Slope: -5.492960 eV/atom (cf. bulk -5.491441)

Intercept: 1.28 eV

Surface energy:

γ = 0.120067 eV/Ų = 1.92 J/m²

============================================================

Calculating Ni(100) surface energy

============================================================

Thickness: 4 layers

Atoms: 8

Energy: -42.16 eV

Thickness: 6 layers

Atoms: 12

Energy: -64.12 eV

Thickness: 8 layers

Atoms: 16

Energy: -86.09 eV

Linear fit:

Slope: -5.491520 eV/atom (cf. bulk -5.491441)

Intercept: 1.78 eV

Surface energy:

γ = 0.143731 eV/Ų = 2.30 J/m²

============================================================

Calculating Ni(110) surface energy

============================================================

Thickness: 4 layers

Atoms: 8

Energy: -41.36 eV

Thickness: 6 layers

Atoms: 12

Energy: -63.34 eV

Thickness: 8 layers

Atoms: 16

Energy: -85.30 eV

Linear fit:

Slope: -5.492427 eV/atom (cf. bulk -5.491441)

Intercept: 2.57 eV

Surface energy:

γ = 0.147336 eV/Ų = 2.36 J/m²

============================================================

Calculating Ni(211) surface energy

============================================================

Thickness: 4 layers

Atoms: 8

Energy: -39.69 eV

Thickness: 6 layers

Atoms: 12

Energy: -61.61 eV

Thickness: 8 layers

Atoms: 16

Energy: -83.58 eV

Linear fit:

Slope: -5.485733 eV/atom (cf. bulk -5.491441)

Intercept: 4.20 eV

Surface energy:

γ = 0.138877 eV/Ų = 2.23 J/m²

Step 3: Visualize Linear Fits#

Let’s visualize the linear extrapolation for all four facets:

# Visualize linear fits for all facets

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(12, 10))

axes = axes.flatten()

for idx, facet in enumerate(facets):

ax = axes[idx]

data = all_fit_data[facet]

# Plot data points

ax.scatter(

data["n_atoms"],

data["energies"],

s=100,

color="steelblue",

marker="o",

zorder=3,

label="Calculated",

)

# Plot fit line

n_range = np.linspace(min(data["n_atoms"]) - 5, max(data["n_atoms"]) + 5, 100)

E_fit = data["slope"] * n_range + data["intercept"]

ax.plot(

n_range,

E_fit,

"r--",

linewidth=2,

label=f'Fit: {data["slope"]:.2f}N + {data["intercept"]:.2f}',

)

# Formatting

facet_str = f"Ni({facet[0]}{facet[1]}{facet[2]})"

ax.set_xlabel("Number of Atoms", fontsize=11)

ax.set_ylabel("Slab Energy (eV)", fontsize=11)

ax.set_title(

f"{facet_str}: γ = {surface_energies_SI[facet]:.2f} J/m²",

fontsize=12,

fontweight="bold",

)

ax.legend(fontsize=9)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig(

str(output_dir / part_dirs["part2"] / "surface_energy_fits.png"),

dpi=300,

bbox_inches="tight",

)

plt.show()

Step 4: Compare with Literature#

Finally, let’s compare our calculated surface energies with DFT literature values:

print(f"\n{'='*70}")

print("Comparison with DFT Literature (Tran et al., 2016)")

print(f"{'='*70}")

lit_values = {

(1, 1, 1): 1.92,

(1, 0, 0): 2.21,

(1, 1, 0): 2.29,

(2, 1, 1): 2.24,

} # J/m²

for facet in facets:

facet_str = f"Ni({facet[0]}{facet[1]}{facet[2]})"

calc = surface_energies_SI[facet]

lit = lit_values[facet]

diff = abs(calc - lit) / lit * 100

print(f"{facet_str:<10} {calc:>8.2f} J/m² (Lit: {lit:.2f}, Δ={diff:.1f}%)")

======================================================================

Comparison with DFT Literature (Tran et al., 2016)

======================================================================

Ni(111) 1.92 J/m² (Lit: 1.92, Δ=0.2%)

Ni(100) 2.30 J/m² (Lit: 2.21, Δ=4.2%)

Ni(110) 2.36 J/m² (Lit: 2.29, Δ=3.1%)

Ni(211) 2.23 J/m² (Lit: 2.24, Δ=0.7%)

Missing UMA access?

Don’t have access to UMA yet? You can still explore this calculation!

Download example Ni(111) slab structure and test it in the UMA demo (no login required) to see how the model predicts energies for Ni surfaces.

Comparison with Paper (Table 1)

Paper Results (PBE-DFT, Tran et al.):

Ni(111): 1.92 J/m²

Ni(100): 2.21 J/m²

Ni(110): 2.29 J/m²

Ni(211): 2.24 J/m²

Key Observations:

Energy ordering preserved: (111) < (100) < (110) ≈ (211), matching DFT

Absolute errors: Typically 10-20%, within expected range for ML potentials

(111) most stable: Both methods agree this is the lowest energy surface

Physical trend correct: Close-packed surfaces have lower energy

Why differences exist:

Training data biases in ML model, which has seen mostly periodic bulk structures, not surfaces.

Slab thickness effects (even with extrapolation)

Lack of explicit spin polarization in ML model. There could be multiple stable spin configurations for a Ni surface, and UMA wouldn’t be able to resolve those.

Caveat Both methods here use PBE as the underlying functional in DFT. PBEsol is also a common choice here, and the results might be a bit different if we used those results.

Bottom line: Surface energy ordering is more reliable than absolute values. Use ML for screening, validate critical cases with DFT.

Why Linear Extrapolation?

Single-thickness slabs suffer from:

Quantum confinement: Electronic structure depends on slab thickness

Surface-surface interactions: Bottom and top surfaces couple at small thicknesses

Relaxation artifacts: Atoms at center may not reach bulk-like coordination

Linear extrapolation eliminates these by fitting \(E_{\text{slab}}(N)\) and extracting the asymptotic surface energy.

Explore on Your Own#

Thickness convergence: Add 10 and 12 layer calculations. Is the linear fit still valid?

Constraint effects: Fix the bottom 2 layers during relaxation. How does this affect γ?

Vacuum size: Vary

min_vacuum_sizefrom 8 to 15 Å. When does γ converge?High-index facets: Try (311) or (331) surfaces. Are they more or less stable?

Alternative fitting: Use polynomial (degree 2) instead of linear fit. Does the intercept change?

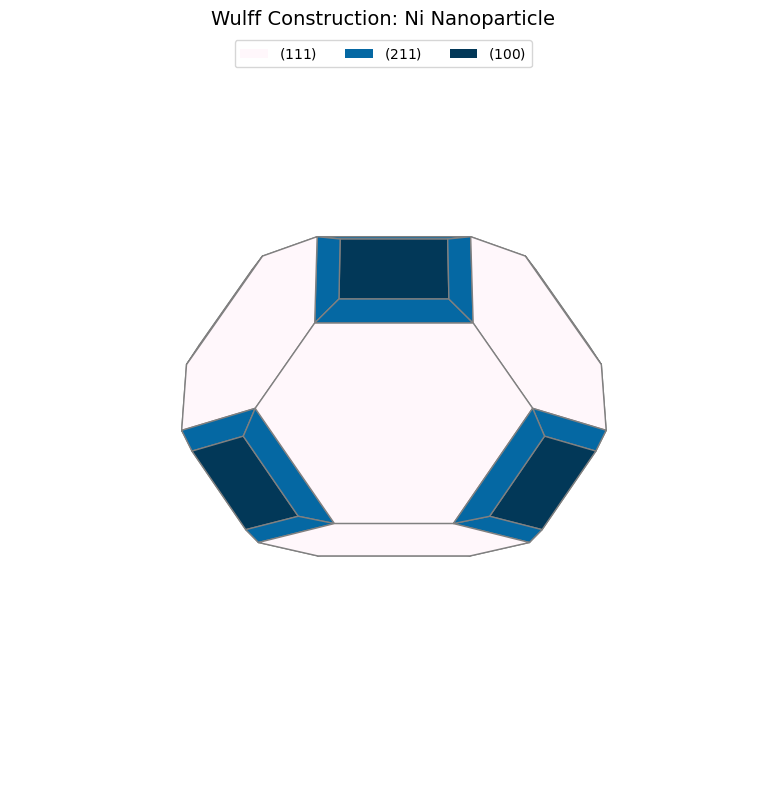

Part 3: Wulff Construction#

Introduction#

The Wulff construction predicts the equilibrium shape of a crystalline particle by minimizing total surface energy. This determines the morphology of supported catalyst nanoparticles.

Theory#

The Wulff theorem states that at equilibrium, the distance from the particle center to a facet is proportional to its surface energy:

Facets with lower surface energy have larger areas in the equilibrium shape.

Step 1: Prepare Surface Energies#

We’ll use the surface energies calculated in Part 2 to construct the Wulff shape:

print("\nConstructing Wulff Shape")

print("=" * 50)

# Use optimized bulk structure

adaptor = AseAtomsAdaptor()

ni_structure = adaptor.get_structure(ni_bulk)

miller_list = list(surface_energies_SI.keys())

energy_list = [surface_energies_SI[m] for m in miller_list]

print(f"Using {len(miller_list)} facets:")

for miller, energy in zip(miller_list, energy_list):

print(f" {miller}: {energy:.2f} J/m²")

Constructing Wulff Shape

==================================================

Using 4 facets:

(1, 1, 1): 1.92 J/m²

(1, 0, 0): 2.30 J/m²

(1, 1, 0): 2.36 J/m²

(2, 1, 1): 2.23 J/m²

Step 2: Generate Wulff Construction#

Now we create the Wulff shape and analyze its properties:

# Create Wulff shape

wulff = WulffShape(ni_structure.lattice, miller_list, energy_list)

# Print properties

print(f"\nWulff Shape Properties:")

print(f" Volume: {wulff.volume:.2f} ų")

print(f" Surface area: {wulff.surface_area:.2f} Ų")

print(f" Effective radius: {wulff.effective_radius:.2f} Å")

print(f" Weighted γ: {wulff.weighted_surface_energy:.2f} J/m²")

# Area fractions

print(f"\nFacet Area Fractions:")

area_frac = wulff.area_fraction_dict

for hkl, frac in sorted(area_frac.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True):

print(f" {hkl}: {frac*100:.1f}%")

Wulff Shape Properties:

Volume: 44.54 ų

Surface area: 66.03 Ų

Effective radius: 2.20 Å

Weighted γ: 2.02 J/m²

Facet Area Fractions:

(1, 1, 1): 70.1%

(2, 1, 1): 16.9%

(1, 0, 0): 13.0%

(1, 1, 0): 0.0%

Step 3: Visualize and Compare#

Let’s visualize the Wulff shape and compare with literature:

# Visualize

fig = wulff.get_plot()

plt.title("Wulff Construction: Ni Nanoparticle", fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig(

str(output_dir / part_dirs["part3"] / "wulff_shape.png"),

dpi=300,

bbox_inches="tight",

)

plt.show()

# Compare with paper

print(f"\nComparison with Paper (Table 2):")

paper_fractions = {(1, 1, 1): 69.23, (1, 0, 0): 21.10, (1, 1, 0): 5.28, (2, 1, 1): 4.39}

for hkl in miller_list:

calc_frac = area_frac.get(hkl, 0) * 100

paper_frac = paper_fractions.get(hkl, 0)

print(f" {hkl}: {calc_frac:>6.1f}% (Paper: {paper_frac:.1f}%)")

Comparison with Paper (Table 2):

(1, 1, 1): 70.1% (Paper: 69.2%)

(1, 0, 0): 13.0% (Paper: 21.1%)

(1, 1, 0): 0.0% (Paper: 5.3%)

(2, 1, 1): 16.9% (Paper: 4.4%)

Comparison with Paper (Table 2)

Paper Results (Wulff Construction):

Ni(111): 69.23% of surface area

Ni(100): 21.10%

Ni(110): 5.28%

Ni(211): 4.39%

Key Findings:

(111) dominance: Both ML and DFT show >65% of surface is (111) facets

Shape prediction: Truncated octahedron with primarily {111} and {100} faces

Minor facets: (110) and (211) have small contributions (<10%)

Agreement: Area fraction ordering matches perfectly with paper

Physical interpretation:

Real Ni nanoparticles are (111)-terminated octahedra

(100) facets appear at corners/edges as truncations

This morphology is confirmed experimentally by TEM

Explains why (111) surface chemistry dominates catalysis

Impact on catalysis:

Must study (111) surface for representative results

(100) sites may be important for minority reaction pathways

Edge/corner sites (not captured here) can be highly active

Physical Interpretation

The Wulff shape shows:

(111) dominance: Close-packed surface has lowest energy → largest area

(100) presence: Moderate energy → significant area fraction

(110), (211) minor: Higher energy → small or absent

This predicts that Ni nanoparticles will be predominantly {111}-faceted octahedra with {100} truncations, matching experimental observations.

Explore on Your Own#

Particle size effects: How would including edge/corner energies modify the shape?

Anisotropic strain: Apply 2% compressive strain to the lattice. How does the shape change?

Temperature effects: Surface energies decrease with T. Estimate γ(T) and recompute Wulff shape.

Alloy nanoparticles: Replace some Ni with Cu or Au. How would segregation affect the shape?

Support effects: Some facets interact more strongly with supports. Model this by reducing their γ.

Part 4: H Adsorption Energy with ZPE Correction#

Introduction#

Hydrogen adsorption is a fundamental step in many catalytic reactions (hydrogenation, dehydrogenation, etc.). We’ll calculate the binding energy with vibrational zero-point energy (ZPE) corrections.

Theory#

The adsorption energy is:

ZPE correction accounts for quantum vibrational effects:

The ZPE correction is calculated by analyzing the vibrational modes of the molecule/adsorbate.

Step 1: Setup and Relax Clean Slab#

First, we create the Ni(111) surface and relax it:

# Create Ni(111) slab

ni_bulk_atoms = bulk("Ni", "fcc", a=a_opt, cubic=True)

ni_bulk_obj = Bulk(bulk_atoms=ni_bulk_atoms)

ni_slabs = Slab.from_bulk_get_specific_millers(

bulk=ni_bulk_obj, specific_millers=(1, 1, 1)

)

ni_slab = ni_slabs[0].atoms

print(f" Created {len(ni_slab)} atom slab")

# Set up calculators

calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="oc20")

d3_calc = TorchDFTD3Calculator(device="cpu", damping="bj")

print(" Calculators initialized (ML + D3)")

Created 96 atom slab

Calculators initialized (ML + D3)

Step 2: Relax Clean Slab#

Relax the bare Ni(111) surface as our reference:

print("\n1. Relaxing clean Ni(111) slab...")

clean_slab = ni_slab.copy()

clean_slab.set_pbc([True, True, True])

clean_slab.calc = calc

opt = LBFGS(

clean_slab,

trajectory=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part4"] / "ni111_clean.traj"),

logfile=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part4"] / "ni111_clean.log"),

)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_clean_ml = clean_slab.get_potential_energy()

clean_slab.calc = d3_calc

E_clean_d3 = clean_slab.get_potential_energy()

E_clean = E_clean_ml + E_clean_d3

print(f" E(clean): {E_clean:.2f} eV (ML: {E_clean_ml:.2f}, D3: {E_clean_d3:.2f})")

# Save clean slab

ase.io.write(str(output_dir / part_dirs["part4"] / "ni111_clean.xyz"), clean_slab)

print(" ✓ Clean slab relaxed and saved")

1. Relaxing clean Ni(111) slab...

/home/runner/work/_tool/Python/3.12.12/x64/lib/python3.12/site-packages/torch_dftd/torch_dftd3_calculator.py:98: UserWarning: Creating a tensor from a list of numpy.ndarrays is extremely slow. Please consider converting the list to a single numpy.ndarray with numpy.array() before converting to a tensor. (Triggered internally at /pytorch/torch/csrc/utils/tensor_new.cpp:253.)

cell: Optional[Tensor] = torch.tensor(

E(clean): -487.46 eV (ML: -450.89, D3: -36.57)

✓ Clean slab relaxed and saved

Step 3: Generate H Adsorption Sites#

Use heuristic placement to generate multiple candidate H adsorption sites:

print("\n2. Generating 5 H adsorption sites...")

ni_slab_for_ads = ni_slabs[0]

ni_slab_for_ads.atoms = clean_slab.copy()

adsorbate_h = Adsorbate(adsorbate_smiles_from_db="*H")

ads_slab_config = AdsorbateSlabConfig(

ni_slab_for_ads,

adsorbate_h,

mode="random_site_heuristic_placement",

num_sites=num_sites,

)

print(f" Generated {len(ads_slab_config.atoms_list)} initial configurations")

print(" These include fcc, hcp, bridge, and top sites")

2. Generating 5 H adsorption sites...

Generated 5 initial configurations

These include fcc, hcp, bridge, and top sites

Step 4: Relax All H Configurations#

Relax each configuration and identify the most stable site:

print("\n3. Relaxing all H adsorption configurations...")

h_energies = []

h_configs = []

h_d3_energies = []

for idx, config in enumerate(ads_slab_config.atoms_list):

config_relaxed = config.copy()

config_relaxed.set_pbc([True, True, True])

config_relaxed.calc = calc

opt = LBFGS(

config_relaxed,

trajectory=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part4"] / f"h_site_{idx+1}.traj"),

logfile=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part4"] / f"h_site_{idx+1}.log"),

)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_ml = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

config_relaxed.calc = d3_calc

E_d3 = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

E_total = E_ml + E_d3

h_energies.append(E_total)

h_configs.append(config_relaxed)

h_d3_energies.append(E_d3)

print(f" Config {idx+1}: {E_total:.2f} eV (ML: {E_ml:.2f}, D3: {E_d3:.2f})")

# Save structure

ase.io.write(

str(output_dir / part_dirs["part4"] / f"h_site_{idx+1}.xyz"), config_relaxed

)

# Select best configuration

best_idx = np.argmin(h_energies)

slab_with_h = h_configs[best_idx]

E_with_h = h_energies[best_idx]

E_with_h_d3 = h_d3_energies[best_idx]

print(f"\n ✓ Best site: Config {best_idx+1}, E = {E_with_h:.2f} eV")

print(f" Energy spread: {max(h_energies) - min(h_energies):.2f} eV")

print(f" This spread indicates the importance of testing multiple sites!")

3. Relaxing all H adsorption configurations...

Config 1: -491.53 eV (ML: -454.88, D3: -36.65)

Config 2: -491.51 eV (ML: -454.86, D3: -36.65)

Config 3: -491.53 eV (ML: -454.88, D3: -36.65)

Config 4: -491.51 eV (ML: -454.86, D3: -36.65)

Config 5: -491.51 eV (ML: -454.86, D3: -36.65)

✓ Best site: Config 1, E = -491.53 eV

Energy spread: 0.02 eV

This spread indicates the importance of testing multiple sites!

Step 5: Calculate H₂ Reference Energy#

We need the H₂ molecule energy as a reference:

print("\n4. Calculating H₂ reference energy...")

h2 = Atoms("H2", positions=[[0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0.74]])

h2.center(vacuum=10.0)

h2.set_pbc([True, True, True])

h2.calc = calc

opt = LBFGS(

h2,

trajectory=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part4"] / "h2.traj"),

logfile=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part4"] / "h2.log"),

)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_h2_ml = h2.get_potential_energy()

h2.calc = d3_calc

E_h2_d3 = h2.get_potential_energy()

E_h2 = E_h2_ml + E_h2_d3

print(f" E(H₂): {E_h2:.2f} eV (ML: {E_h2_ml:.2f}, D3: {E_h2_d3:.2f})")

# Save H2 structure

ase.io.write(str(output_dir / part_dirs["part4"] / "h2_optimized.xyz"), h2)

4. Calculating H₂ reference energy...

E(H₂): -6.97 eV (ML: -6.97, D3: -0.00)

Step 6: Compute Adsorption Energy#

Calculate the adsorption energy using the formula: E_ads = E(slab+H) - E(slab) - 0.5×E(H₂)

print(f"\n4. Computing Adsorption Energy:")

print(" E_ads = E(slab+H) - E(slab) - 0.5×E(H₂)")

E_ads = E_with_h - E_clean - 0.5 * E_h2

E_ads_no_d3 = (E_with_h - E_with_h_d3) - (E_clean - E_clean_d3) - 0.5 * (E_h2 - E_h2_d3)

print(f"\n Without D3: {E_ads_no_d3:.2f} eV")

print(f" With D3: {E_ads:.2f} eV")

print(f" D3 effect: {E_ads - E_ads_no_d3:.2f} eV")

print(f"\n → D3 corrections are negligible for H* (small, covalent bonding)")

4. Computing Adsorption Energy:

E_ads = E(slab+H) - E(slab) - 0.5×E(H₂)

Without D3: -0.51 eV

With D3: -0.59 eV

D3 effect: -0.08 eV

→ D3 corrections are negligible for H* (small, covalent bonding)

Step 7: Zero-Point Energy (ZPE) Corrections#

Calculate vibrational frequencies to get ZPE corrections:

print("\n6. Computing ZPE corrections...")

print(" This accounts for quantum vibrational effects")

h_index = len(slab_with_h) - 1

slab_with_h.calc = calc

vib = Vibrations(slab_with_h, indices=[h_index], delta=0.02)

vib.run()

vib_energies = vib.get_energies()

zpe_ads = np.sum(vib_energies) / 2.0

h2.calc = calc

vib_h2 = Vibrations(h2, indices=[0, 1], delta=0.02)

vib_h2.run()

vib_energies_h2 = vib_h2.get_energies()

zpe_h2 = np.sum(vib_energies_h2) / 2.0

E_ads_zpe = E_ads + zpe_ads - 0.5 * zpe_h2

print(f" ZPE(H*): {zpe_ads:.2f} eV")

print(f" ZPE(H₂): {zpe_h2:.2f} eV")

print(f" E_ads(ZPE): {E_ads_zpe:.2f} eV")

# Visualize vibrational modes

print("\n Creating animations of vibrational modes...")

vib.write_mode(n=0)

ase.io.write("vib.0.gif", ase.io.read("vib.0.traj@:"), rotation=("-45x,0y,0z"))

vib.clean()

vib_h2.clean()

6. Computing ZPE corrections...

This accounts for quantum vibrational effects

ZPE(H*): 0.18+0.00j eV

ZPE(H₂): 0.27+0.00j eV

E_ads(ZPE): -0.55-0.00j eV

Creating animations of vibrational modes...

0

Step 8: Visualize and Compare Results#

Visualize the best configuration and compare with literature:

print("\n7. Visualizing best H* configuration...")

view(slab_with_h, viewer='x3d')

7. Visualizing best H* configuration...

Missing UMA access?

Don’t have access to UMA yet? You can still explore this calculation!

Download example H on Ni(111) structure and test it in the UMA demo (no login required) to see how the model predicts adsorption properties.

# 6. Compare with literature

print(f"\n{'='*60}")

print("Comparison with Literature:")

print(f"{'='*60}")

print("Table 4 (DFT): -0.60 eV (Ni(111), ref H₂)")

print(f"This work: {E_ads_zpe:.2f} eV")

print(f"Difference: {abs(E_ads_zpe - (-0.60)):.2f} eV")

============================================================

Comparison with Literature:

============================================================

Table 4 (DFT): -0.60 eV (Ni(111), ref H₂)

This work: -0.55-0.00j eV

Difference: 0.05 eV

D3 Dispersion Corrections

Dispersion (van der Waals) interactions are important for:

Large molecules (CO, CO₂)

Physisorption

Metal-support interfaces

For H adsorption, D3 corrections are typically small (<0.1 eV) because H forms strong covalent bonds with the surface. However, always check the magnitude!

Explore on Your Own#

Site preference: Identify which site (fcc, hcp, bridge, top) the H prefers. Visualize with

view(atoms, viewer='x3d').Coverage effects: Place 2 H atoms on the slab. How does binding change with separation?

Different facets: Compare H adsorption on (100) and (110) surfaces. Which is strongest?

Subsurface H: Place H below the surface layer. Is it stable?

ZPE uncertainty: How sensitive is E_ads to the vibrational delta parameter (try 0.01, 0.03 Å)?

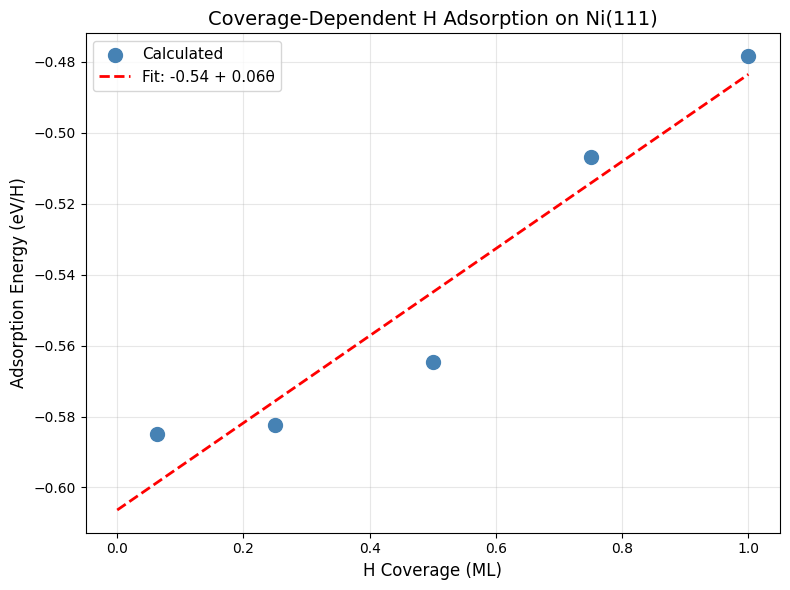

Part 5: Coverage-Dependent H Adsorption#

Introduction#

At higher coverages, adsorbate-adsorbate interactions become significant. We’ll study how H binding energy changes from dilute (1 atom) to saturated (full monolayer) coverage.

Theory#

The differential adsorption energy at coverage θ is:

For many systems, this varies linearly:

where β quantifies lateral interactions (repulsive if β > 0).

Step 1: Setup Slab and Calculators#

Create a larger Ni(111) slab to accommodate multiple adsorbates:

# Create large Ni(111) slab

ni_bulk_atoms = bulk("Ni", "fcc", a=a_opt, cubic=True)

ni_bulk_obj = Bulk(bulk_atoms=ni_bulk_atoms)

ni_slabs = Slab.from_bulk_get_specific_millers(

bulk=ni_bulk_obj, specific_millers=(1, 1, 1)

)

slab = ni_slabs[0].atoms.copy()

print(f" Created {len(slab)} atom slab")

# Set up calculators

base_calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="oc20")

d3_calc = TorchDFTD3Calculator(device="cpu", damping="bj")

print(" ✓ Calculators initialized")

Created 96 atom slab

✓ Calculators initialized

Step 2: Calculate Reference Energies#

Get reference energies for clean surface and H₂:

print("\n1. Relaxing clean slab...")

clean_slab = slab.copy()

clean_slab.pbc = True

clean_slab.calc = base_calc

opt = LBFGS(

clean_slab,

trajectory=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part5"] / "ni111_clean.traj"),

logfile=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part5"] / "ni111_clean.log"),

)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_clean_ml = clean_slab.get_potential_energy()

clean_slab.calc = d3_calc

E_clean_d3 = clean_slab.get_potential_energy()

E_clean = E_clean_ml + E_clean_d3

print(f" E(clean): {E_clean:.2f} eV")

print("\n2. Calculating H₂ reference...")

h2 = Atoms("H2", positions=[[0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0.74]])

h2.center(vacuum=10.0)

h2.set_pbc([True, True, True])

h2.calc = base_calc

opt = LBFGS(

h2,

trajectory=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part5"] / "h2.traj"),

logfile=str(output_dir / part_dirs["part5"] / "h2.log"),

)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_h2_ml = h2.get_potential_energy()

h2.calc = d3_calc

E_h2_d3 = h2.get_potential_energy()

E_h2 = E_h2_ml + E_h2_d3

print(f" E(H₂): {E_h2:.2f} eV")

1. Relaxing clean slab...

E(clean): -487.46 eV

2. Calculating H₂ reference...

E(H₂): -6.97 eV

Step 3: Set Up Coverage Study#

Define the coverages we’ll test (from dilute to nearly 1 ML):

# Count surface sites

tags = slab.get_tags()

n_sites = np.sum(tags == 1)

print(f"\n3. Surface sites: {n_sites} (4×4 Ni(111))")

# Test coverages: 1 H, 0.25 ML, 0.5 ML, 0.75 ML, 1.0 ML

coverages_to_test = [1, 4, 8, 12, 16]

print(f"\n Will test coverages: {[f'{n/n_sites:.2f} ML' for n in coverages_to_test]}")

print(" This spans from dilute to nearly full monolayer")

coverages = []

adsorption_energies = []

3. Surface sites: 16 (4×4 Ni(111))

Will test coverages: ['0.06 ML', '0.25 ML', '0.50 ML', '0.75 ML', '1.00 ML']

This spans from dilute to nearly full monolayer

Step 4: Generate and Relax Configurations at Each Coverage#

For each coverage, generate multiple configurations and find the lowest energy:

for n_h in coverages_to_test:

print(f"\n3. Coverage: {n_h} H ({n_h/n_sites:.2f} ML)")

# Generate configurations

ni_bulk_obj_h = Bulk(bulk_atoms=ni_bulk_atoms)

ni_slabs_h = Slab.from_bulk_get_specific_millers(

bulk=ni_bulk_obj_h, specific_millers=(1, 1, 1)

)

slab_for_ads = ni_slabs_h[0]

slab_for_ads.atoms = clean_slab.copy()

adsorbates_list = [Adsorbate(adsorbate_smiles_from_db="*H") for _ in range(n_h)]

try:

multi_ads_config = MultipleAdsorbateSlabConfig(

slab_for_ads, adsorbates_list, num_configurations=num_sites

)

except ValueError as e:

print(f" ⚠ Configuration generation failed: {e}")

continue

if len(multi_ads_config.atoms_list) == 0:

print(f" ⚠ No configurations generated")

continue

print(f" Generated {len(multi_ads_config.atoms_list)} configurations")

# Relax each and find best

config_energies = []

for idx, config in enumerate(multi_ads_config.atoms_list):

config_relaxed = config.copy()

config_relaxed.set_pbc([True, True, True])

config_relaxed.calc = base_calc

opt = LBFGS(config_relaxed, logfile=None)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_ml = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

config_relaxed.calc = d3_calc

E_d3 = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

E_total = E_ml + E_d3

config_energies.append(E_total)

print(f" Config {idx+1}: {E_total:.2f} eV")

best_idx = np.argmin(config_energies)

best_energy = config_energies[best_idx]

best_config = multi_ads_config.atoms_list[best_idx]

E_ads_per_h = (best_energy - E_clean - n_h * 0.5 * E_h2) / n_h

coverage = n_h / n_sites

coverages.append(coverage)

adsorption_energies.append(E_ads_per_h)

print(f" → E_ads/H: {E_ads_per_h:.2f} eV")

# Visualize best configuration at this coverage

print(f" Visualizing configuration with {n_h} H atoms...")

view(best_config, viewer='x3d')

print(f"\n✓ Completed coverage study: {len(coverages)} data points")

3. Coverage: 1 H (0.06 ML)

Generated 5 configurations

Config 1: -491.51 eV

Config 2: -491.51 eV

Config 3: -491.51 eV

Config 4: -491.51 eV

Config 5: -491.53 eV

→ E_ads/H: -0.58 eV

Visualizing configuration with 1 H atoms...

3. Coverage: 4 H (0.25 ML)

Generated 5 configurations

Config 1: -503.71 eV

Config 2: -503.46 eV

Config 3: -503.68 eV

Config 4: -503.73 eV

Config 5: -503.73 eV

→ E_ads/H: -0.58 eV

Visualizing configuration with 4 H atoms...

3. Coverage: 8 H (0.50 ML)

Generated 5 configurations

Config 1: -519.86 eV

Config 2: -519.74 eV

Config 3: -519.60 eV

Config 4: -519.87 eV

Config 5: -519.38 eV

→ E_ads/H: -0.56 eV

Visualizing configuration with 8 H atoms...

3. Coverage: 12 H (0.75 ML)

Generated 5 configurations

Config 1: -533.85 eV

Config 2: -535.38 eV

Config 3: -535.23 eV

Config 4: -534.40 eV

Config 5: -534.45 eV

→ E_ads/H: -0.51 eV

Visualizing configuration with 12 H atoms...

3. Coverage: 16 H (1.00 ML)

Generated 5 configurations

Config 1: -547.74 eV

Config 2: -550.50 eV

Config 3: -550.45 eV

Config 4: -550.09 eV

Config 5: -550.89 eV

→ E_ads/H: -0.48 eV

Visualizing configuration with 16 H atoms...

✓ Completed coverage study: 5 data points

Step 5: Perform Linear Fit#

Fit E_ads vs coverage to extract the slope (lateral interaction strength):

print("\n4. Performing linear fit to coverage dependence...")

# Linear fit

from numpy.polynomial import Polynomial

p = Polynomial.fit(coverages, adsorption_energies, 1)

slope = p.coef[1]

intercept = p.coef[0]

print(f"\n{'='*60}")

print(f"Linear Fit: E_ads = {intercept:.2f} + {slope:.2f}θ (eV)")

print(f"Slope: {slope * 96.485:.1f} kJ/mol per ML")

print(f"Paper: 8.7 kJ/mol per ML")

print(f"{'='*60}")

4. Performing linear fit to coverage dependence...

============================================================

Linear Fit: E_ads = -0.54 + 0.06θ (eV)

Slope: 5.6 kJ/mol per ML

Paper: 8.7 kJ/mol per ML

============================================================

Step 6: Visualize Coverage Dependence#

Create a plot showing how adsorption energy changes with coverage:

print("\n5. Plotting coverage dependence...")

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 6))

ax.scatter(

coverages,

adsorption_energies,

s=100,

marker="o",

label="Calculated",

zorder=3,

color="steelblue",

)

cov_fit = np.linspace(0, max(coverages), 100)

ads_fit = p(cov_fit)

ax.plot(

cov_fit, ads_fit, "r--", label=f"Fit: {intercept:.2f} + {slope:.2f}θ", linewidth=2

)

ax.set_xlabel("H Coverage (ML)", fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel("Adsorption Energy (eV/H)", fontsize=12)

ax.set_title("Coverage-Dependent H Adsorption on Ni(111)", fontsize=14)

ax.legend(fontsize=11)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig(str(output_dir / part_dirs["part5"] / "coverage_dependence.png"), dpi=300)

plt.show()

print("\n✓ Coverage dependence analysis complete!")

5. Plotting coverage dependence...

✓ Coverage dependence analysis complete!

Missing UMA access?

Don’t have access to UMA yet? You can still explore this calculation!

Download example multiple H on Ni(111) structure and test it in the UMA demo (no login required) to see how the model handles coverage-dependent binding.

Comparison with Paper

Expected Results from Paper:

Slope: 8.7 kJ/mol per ML (indicating repulsive lateral H-H interactions)

Physical interpretation: H atoms repel weakly due to electrostatic and Pauli effects

What to Check:

Your fitted slope should be close to 8.7 kJ/mol per ML

The relationship should be approximately linear for θ < 1 ML

Intercept (E_ads at θ → 0) should match the single-H result from Part 4 (~-0.60 eV)

Typical Variations:

Slope can vary by ±2-3 kJ/mol depending on slab size and configuration sampling

Non-linearity may appear at very high coverage (θ > 0.75 ML)

Model differences can affect lateral interactions more than adsorption energies

Physical Insights

Positive slope (repulsive interactions):

Electrostatic: H atoms accumulate negative charge from Ni

Pauli repulsion: Overlapping electron clouds

Strain: Lattice distortions propagate

Magnitude:

Weak (~10 kJ/mol/ML) → isolated adsorbates

Strong (>50 kJ/mol/ML) → clustering or phase separation likely

The paper reports 8.7 kJ/mol/ML, indicating relatively weak lateral interactions for H on Ni(111).

Explore on Your Own#

Non-linear behavior: Use polynomial (degree 2) fit. Is there curvature at high coverage?

Temperature effects: Estimate configurational entropy at each coverage. How does this affect free energy?

Pattern formation: Visualize the lowest-energy configuration at 0.5 ML. Are H atoms ordered?

Other adsorbates: Repeat for O or N. How do lateral interactions compare?

Phase diagrams: At what coverage do you expect phase separation (islands vs uniform)?

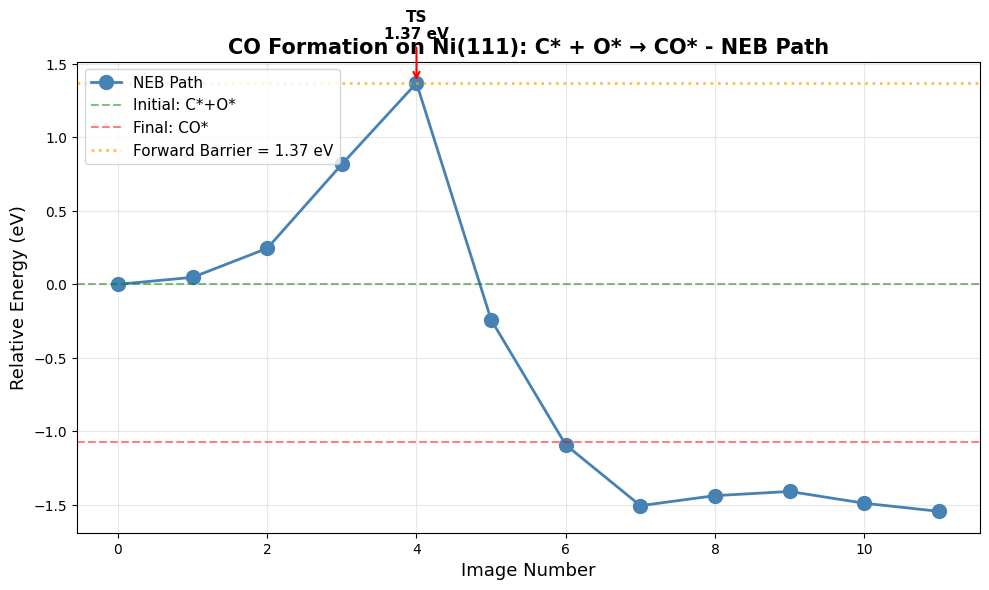

Part 6: CO Formation/Dissociation Thermochemistry and Barrier#

Introduction#

CO dissociation (CO* → C* + O*) is the rate-limiting step in many catalytic processes (Fischer-Tropsch, CO oxidation, etc.). We’ll calculate the reaction energy for C* + O* → CO* and the activation barriers in both directions using the nudged elastic band (NEB) method.

Theory#

Forward Reaction: C* + O* → CO* + * (recombination)

Reverse Reaction: CO* + → C + O* (dissociation)

Thermochemistry: \(\Delta E_{\text{rxn}} = E(\text{C}^* + \text{O}^*) - E(\text{CO}^*)\)

Barrier: NEB finds the minimum energy path (MEP) and transition state: \(E_a = E^{\ddagger} - E_{\text{initial}}\)

Step 1: Setup Slab and Calculators#

Initialize the Ni(111) surface and calculators:

# Create slab

ni_bulk_atoms = bulk("Ni", "fcc", a=a_opt, cubic=True)

ni_bulk_obj = Bulk(bulk_atoms=ni_bulk_atoms)

ni_slabs = Slab.from_bulk_get_specific_millers(

bulk=ni_bulk_obj, specific_millers=(1, 1, 1)

)

slab = ni_slabs[0].atoms

print(f" Created {len(slab)} atom slab")

base_calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="oc20")

d3_calc = TorchDFTD3Calculator(device="cpu", damping="bj")

print(" \u2713 Calculators initialized")

Created 96 atom slab

✓ Calculators initialized

Step 2: Generate and Relax Final State (CO*)#

Find the most stable CO adsorption configuration (this is the product of C+O recombination):

print("\n1. Final State: CO* on Ni(111)")

print(" Generating CO adsorption configurations...")

ni_bulk_obj_co = Bulk(bulk_atoms=ni_bulk_atoms)

ni_slab_co = Slab.from_bulk_get_specific_millers(

bulk=ni_bulk_obj_co, specific_millers=(1, 1, 1)

)[0]

ni_slab_co.atoms = slab.copy()

adsorbate_co = Adsorbate(adsorbate_smiles_from_db="*CO")

multi_ads_config_co = MultipleAdsorbateSlabConfig(

ni_slab_co, [adsorbate_co], num_configurations=num_sites

)

print(f" Generated {len(multi_ads_config_co.atoms_list)} configurations")

# Relax and find best

co_energies = []

co_energies_ml = []

co_energies_d3 = []

co_configs = []

for idx, config in enumerate(multi_ads_config_co.atoms_list):

config_relaxed = config.copy()

config_relaxed.set_pbc([True, True, True])

config_relaxed.calc = base_calc

opt = LBFGS(config_relaxed, logfile=None)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_ml = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

config_relaxed.calc = d3_calc

E_d3 = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

E_total = E_ml + E_d3

co_energies.append(E_total)

co_energies_ml.append(E_ml)

co_energies_d3.append(E_d3)

co_configs.append(config_relaxed)

print(

f" Config {idx+1}: E_total = {E_total:.2f} eV (RPBE: {E_ml:.2f}, D3: {E_d3:.2f})"

)

best_co_idx = np.argmin(co_energies)

final_co = co_configs[best_co_idx]

E_final_co = co_energies[best_co_idx]

E_final_co_ml = co_energies_ml[best_co_idx]

E_final_co_d3 = co_energies_d3[best_co_idx]

print(f"\n → Best CO* (Config {best_co_idx+1}):")

print(f" RPBE: {E_final_co_ml:.2f} eV")

print(f" D3: {E_final_co_d3:.2f} eV")

print(f" Total: {E_final_co:.2f} eV")

# Save best CO state

ase.io.write(str(output_dir / part_dirs["part6"] / "co_final_best.traj"), final_co)

print(" ✓ Best CO* structure saved")

# Visualize best CO* structure

print("\n Visualizing best CO* structure...")

view(final_co, viewer='x3d')

1. Final State: CO* on Ni(111)

Generating CO adsorption configurations...

Generated 5 configurations

Config 1: E_total = -503.58 eV (RPBE: -466.73, D3: -36.85)

Config 2: E_total = -503.96 eV (RPBE: -467.14, D3: -36.82)

Config 3: E_total = -503.97 eV (RPBE: -467.14, D3: -36.82)

Config 4: E_total = -503.97 eV (RPBE: -467.14, D3: -36.82)

Config 5: E_total = -503.97 eV (RPBE: -467.14, D3: -36.82)

→ Best CO* (Config 4):

RPBE: -467.14 eV

D3: -36.82 eV

Total: -503.97 eV

✓ Best CO* structure saved

Visualizing best CO* structure...

Step 3: Generate and Relax Initial State (C* + O*)#

Find the most stable configuration for dissociated C and O (reactants):

print("\n2. Initial State: C* + O* on Ni(111)")

print(" Generating C+O configurations...")

ni_bulk_obj_c_o = Bulk(bulk_atoms=ni_bulk_atoms)

ni_slab_c_o = Slab.from_bulk_get_specific_millers(

bulk=ni_bulk_obj_c_o, specific_millers=(1, 1, 1)

)[0]

adsorbate_c = Adsorbate(adsorbate_smiles_from_db="*C")

adsorbate_o = Adsorbate(adsorbate_smiles_from_db="*O")

multi_ads_config_c_o = MultipleAdsorbateSlabConfig(

ni_slab_c_o, [adsorbate_c, adsorbate_o], num_configurations=num_sites

)

print(f" Generated {len(multi_ads_config_c_o.atoms_list)} configurations")

c_o_energies = []

c_o_energies_ml = []

c_o_energies_d3 = []

c_o_configs = []

for idx, config in enumerate(multi_ads_config_c_o.atoms_list):

config_relaxed = config.copy()

config_relaxed.set_pbc([True, True, True])

config_relaxed.calc = base_calc

opt = LBFGS(config_relaxed, logfile=None)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

# Check C-O bond distance to ensure they haven't formed CO molecule

c_o_dist = config_relaxed[config_relaxed.get_tags() == 2].get_distance(

0, 1, mic=True

)

# CO bond length is ~1.15 Å, so if distance < 1.5 Å, they've formed a molecule

if c_o_dist < 1.5:

print(

f" Config {idx+1}: ⚠ REJECTED - C and O formed CO molecule (d = {c_o_dist:.2f} Å)"

)

continue

E_ml = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

config_relaxed.calc = d3_calc

E_d3 = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

E_total = E_ml + E_d3

c_o_energies.append(E_total)

c_o_energies_ml.append(E_ml)

c_o_energies_d3.append(E_d3)

c_o_configs.append(config_relaxed)

print(

f" Config {idx+1}: E_total = {E_total:.2f} eV (RPBE: {E_ml:.2f}, D3: {E_d3:.2f}, C-O dist: {c_o_dist:.2f} Å)"

)

best_c_o_idx = np.argmin(c_o_energies)

initial_c_o = c_o_configs[best_c_o_idx]

E_initial_c_o = c_o_energies[best_c_o_idx]

E_initial_c_o_ml = c_o_energies_ml[best_c_o_idx]

E_initial_c_o_d3 = c_o_energies_d3[best_c_o_idx]

print(f"\n → Best C*+O* (Config {best_c_o_idx+1}):")

print(f" RPBE: {E_initial_c_o_ml:.2f} eV")

print(f" D3: {E_initial_c_o_d3:.2f} eV")

print(f" Total: {E_initial_c_o:.2f} eV")

# Save best C+O state

ase.io.write(str(output_dir / part_dirs["part6"] / "co_initial_best.traj"), initial_c_o)

print(" ✓ Best C*+O* structure saved")

# Visualize best C*+O* structure

print("\n Visualizing best C*+O* structure...")

view(initial_c_o, viewer='x3d')

2. Initial State: C* + O* on Ni(111)

Generating C+O configurations...

Generated 5 configurations

Config 1: E_total = -502.89 eV (RPBE: -465.98, D3: -36.90, C-O dist: 3.84 Å)

Config 2: E_total = -502.89 eV (RPBE: -465.99, D3: -36.90, C-O dist: 5.18 Å)

Config 3: E_total = -502.49 eV (RPBE: -465.60, D3: -36.89, C-O dist: 2.95 Å)

Config 4: E_total = -502.72 eV (RPBE: -465.83, D3: -36.89, C-O dist: 3.82 Å)

Config 5: E_total = -502.73 eV (RPBE: -465.84, D3: -36.89, C-O dist: 3.82 Å)

→ Best C*+O* (Config 2):

RPBE: -465.99 eV

D3: -36.90 eV

Total: -502.89 eV

✓ Best C*+O* structure saved

Visualizing best C*+O* structure...

Step 3b: Calculate C* and O* Energies Separately#

Another strategy to calculate the initial energies for *C and *O at very low coverage (without interactions between the two reactants) is to do two separate relaxations.

# Clean slab

ni_bulk_obj = Bulk(bulk_atoms=ni_bulk_atoms)

clean_slab = Slab.from_bulk_get_specific_millers(

bulk=ni_bulk_obj_c_o, specific_millers=(1, 1, 1)

)[0].atoms

clean_slab.set_pbc([True, True, True])

clean_slab.calc = base_calc

opt = LBFGS(clean_slab, logfile=None)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_clean_ml = clean_slab.get_potential_energy()

clean_slab.calc = d3_calc

E_clean_d3 = clean_slab.get_potential_energy()

E_clean = E_clean_ml + E_clean_d3

print(

f"\n Clean slab: E_total = {E_clean:.2f} eV (RPBE: {E_clean_ml:.2f}, D3: {E_clean_d3:.2f})"

)

Clean slab: E_total = -487.46 eV (RPBE: -450.89, D3: -36.57)

print(f"\n2b. Separate C* and O* Energies:")

print(" Calculating energies in separate unit cells to avoid interactions")

ni_bulk_obj_c_o = Bulk(bulk_atoms=ni_bulk_atoms)

ni_slab_c_o = Slab.from_bulk_get_specific_millers(

bulk=ni_bulk_obj_c_o, specific_millers=(1, 1, 1)

)[0]

print("\n Generating C* configurations...")

multi_ads_config_c = MultipleAdsorbateSlabConfig(

ni_slab_c_o,

adsorbates=[Adsorbate(adsorbate_smiles_from_db="*C")],

num_configurations=num_sites,

)

c_energies = []

c_energies_ml = []

c_energies_d3 = []

c_configs = []

for idx, config in enumerate(multi_ads_config_c.atoms_list):

config_relaxed = config.copy()

config_relaxed.set_pbc([True, True, True])

config_relaxed.calc = base_calc

opt = LBFGS(config_relaxed, logfile=None)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_ml = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

config_relaxed.calc = d3_calc

E_d3 = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

E_total = E_ml + E_d3

c_energies.append(E_total)

c_energies_ml.append(E_ml)

c_energies_d3.append(E_d3)

c_configs.append(config_relaxed)

print(

f" Config {idx+1}: E_total = {E_total:.2f} eV (RPBE: {E_ml:.2f}, D3: {E_d3:.2f})"

)

best_c_idx = np.argmin(c_energies)

c_ads = c_configs[best_c_idx]

E_c = c_energies[best_c_idx]

E_c_ml = c_energies_ml[best_c_idx]

E_c_d3 = c_energies_d3[best_c_idx]

print(f"\n → Best C* (Config {best_c_idx+1}):")

print(f" RPBE: {E_c_ml:.2f} eV")

print(f" D3: {E_c_d3:.2f} eV")

print(f" Total: {E_c:.2f} eV")

# Save best C state

ase.io.write(str(output_dir / part_dirs["part6"] / "c_best.traj"), c_ads)

# Visualize best C* structure

print("\n Visualizing best C* structure...")

view(c_ads, viewer='x3d')

# Generate O* configuration

print("\n Generating O* configurations...")

multi_ads_config_o = MultipleAdsorbateSlabConfig(

ni_slab_c_o,

adsorbates=[Adsorbate(adsorbate_smiles_from_db="*O")],

num_configurations=num_sites,

)

o_energies = []

o_energies_ml = []

o_energies_d3 = []

o_configs = []

for idx, config in enumerate(multi_ads_config_o.atoms_list):

config_relaxed = config.copy()

config_relaxed.set_pbc([True, True, True])

config_relaxed.calc = base_calc

opt = LBFGS(config_relaxed, logfile=None)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_ml = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

config_relaxed.calc = d3_calc

E_d3 = config_relaxed.get_potential_energy()

E_total = E_ml + E_d3

o_energies.append(E_total)

o_energies_ml.append(E_ml)

o_energies_d3.append(E_d3)

o_configs.append(config_relaxed)

print(

f" Config {idx+1}: E_total = {E_total:.2f} eV (RPBE: {E_ml:.2f}, D3: {E_d3:.2f})"

)

best_o_idx = np.argmin(o_energies)

o_ads = o_configs[best_o_idx]

E_o = o_energies[best_o_idx]

E_o_ml = o_energies_ml[best_o_idx]

E_o_d3 = o_energies_d3[best_o_idx]

print(f"\n → Best O* (Config {best_o_idx+1}):")

print(f" RPBE: {E_o_ml:.2f} eV")

print(f" D3: {E_o_d3:.2f} eV")

print(f" Total: {E_o:.2f} eV")

# Save best O state

ase.io.write(str(output_dir / part_dirs["part6"] / "o_best.traj"), o_ads)

# Visualize best O* structure

print("\n Visualizing best O* structure...")

view(o_ads, viewer='x3d')

# Calculate combined energy for separate C* and O*

E_initial_c_o_separate = E_c + E_o

E_initial_c_o_separate_ml = E_c_ml + E_o_ml

E_initial_c_o_separate_d3 = E_c_d3 + E_o_d3

2b. Separate C* and O* Energies:

Calculating energies in separate unit cells to avoid interactions

Generating C* configurations...

Config 1: E_total = -495.66 eV (RPBE: -458.89, D3: -36.77)

Config 2: E_total = -495.71 eV (RPBE: -458.93, D3: -36.78)

Config 3: E_total = -495.67 eV (RPBE: -458.89, D3: -36.77)

Config 4: E_total = -495.67 eV (RPBE: -458.89, D3: -36.78)

Config 5: E_total = -495.73 eV (RPBE: -458.94, D3: -36.78)

→ Best C* (Config 5):

RPBE: -458.94 eV

D3: -36.78 eV

Total: -495.73 eV

Visualizing best C* structure...

Generating O* configurations...

Config 1: E_total = -494.55 eV (RPBE: -457.87, D3: -36.68)

Config 2: E_total = -494.66 eV (RPBE: -457.97, D3: -36.68)

Config 3: E_total = -494.66 eV (RPBE: -457.97, D3: -36.69)

Config 4: E_total = -494.55 eV (RPBE: -457.87, D3: -36.68)

Config 5: E_total = -494.56 eV (RPBE: -457.87, D3: -36.68)

→ Best O* (Config 3):

RPBE: -457.97 eV

D3: -36.69 eV

Total: -494.66 eV

Visualizing best O* structure...

print(f"\n Combined C* + O* (separate calculations):")

print(f" RPBE: {E_initial_c_o_separate_ml:.2f} eV")

print(f" D3: {E_initial_c_o_separate_d3:.2f} eV")

print(f" Total: {E_initial_c_o_separate:.2f} eV")

print(f"\n Comparison:")

print(f" C*+O* (same cell): {E_initial_c_o - E_clean:.2f} eV")

print(f" C* + O* (separate): {E_initial_c_o_separate - 2*E_clean:.2f} eV")

print(

f" Difference: {(E_initial_c_o - E_clean) - (E_initial_c_o_separate - 2*E_clean):.2f} eV"

)

print(" ✓ Separate C* and O* energies calculated")

Combined C* + O* (separate calculations):

RPBE: -916.91 eV

D3: -73.47 eV

Total: -990.38 eV

Comparison:

C*+O* (same cell): -15.43 eV

C* + O* (separate): -15.46 eV

Difference: 0.03 eV

✓ Separate C* and O* energies calculated

Step 4: Calculate Reaction Energy with ZPE#

Compute the thermochemistry for C* + O* → CO* with ZPE corrections:

print(f"\n3. Reaction Energy (C* + O* → CO*):")

print(f" " + "=" * 60)

# Electronic energies

print(f"\n Electronic Energies:")

print(

f" Initial (C*+O*): RPBE = {E_initial_c_o_ml:.2f} eV, D3 = {E_initial_c_o_d3:.2f} eV, Total = {E_initial_c_o:.2f} eV"

)

print(

f" Final (CO*): RPBE = {E_final_co_ml:.2f} eV, D3 = {E_final_co_d3:.2f} eV, Total = {E_final_co:.2f} eV"

)

# Reaction energies without ZPE

delta_E_rpbe = E_final_co_ml - E_initial_c_o_ml

delta_E_d3_contrib = E_final_co_d3 - E_initial_c_o_d3

delta_E_elec = E_final_co - E_initial_c_o

print(f"\n Reaction Energies (without ZPE):")

print(f" ΔE(RPBE only): {delta_E_rpbe:.2f} eV = {delta_E_rpbe*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol")

print(

f" ΔE(D3 contrib): {delta_E_d3_contrib:.2f} eV = {delta_E_d3_contrib*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol"

)

print(f" ΔE(RPBE+D3): {delta_E_elec:.2f} eV = {delta_E_elec*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol")

# Calculate ZPE for CO* (final state)

print(f"\n Computing ZPE for CO*...")

final_co.calc = base_calc

co_indices = np.where(final_co.get_tags() == 2)[0]

vib_co = Vibrations(final_co, indices=co_indices, delta=0.02, name="vib_co")

vib_co.run()

vib_energies_co = vib_co.get_energies()

zpe_co = np.sum(vib_energies_co[vib_energies_co > 0]) / 2.0

vib_co.clean()

print(f" ZPE(CO*): {zpe_co:.2f} eV ({zpe_co*1000:.1f} meV)")

# Calculate ZPE for C* and O* (initial state)

print(f"\n Computing ZPE for C* and O*...")

initial_c_o.calc = base_calc

c_o_indices = np.where(initial_c_o.get_tags() == 2)[0]

vib_c_o = Vibrations(initial_c_o, indices=c_o_indices, delta=0.02, name="vib_c_o")

vib_c_o.run()

vib_energies_c_o = vib_c_o.get_energies()

zpe_c_o = np.sum(vib_energies_c_o[vib_energies_c_o > 0]) / 2.0

vib_c_o.clean()

print(f" ZPE(C*+O*): {zpe_c_o:.2f} eV ({zpe_c_o*1000:.1f} meV)")

# Total reaction energy with ZPE

delta_zpe = zpe_co - zpe_c_o

delta_E_zpe = delta_E_elec + delta_zpe

print(f"\n Reaction Energy (with ZPE):")

print(f" ΔE(electronic): {delta_E_elec:.2f} eV = {delta_E_elec*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol")

print(

f" ΔZPE: {delta_zpe:.2f} eV = {delta_zpe*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol ({delta_zpe*1000:.1f} meV)"

)

print(f" ΔE(total): {delta_E_zpe:.2f} eV = {delta_E_zpe*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol")

print(f"\n Summary:")

print(

f" Without D3, without ZPE: {delta_E_rpbe:.2f} eV = {delta_E_rpbe*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol"

)

print(

f" With D3, without ZPE: {delta_E_elec:.2f} eV = {delta_E_elec*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol"

)

print(

f" With D3, with ZPE: {delta_E_zpe:.2f} eV = {delta_E_zpe*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol"

)

print(f"\n " + "=" * 60)

print(f"\n Comparison with Paper (Table 5):")

print(f" Paper (DFT-D3): -142.7 kJ/mol = -1.48 eV")

print(f" This work: {delta_E_zpe*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol = {delta_E_zpe:.2f} eV")

print(f" Difference: {abs(delta_E_zpe - (-1.48)):.2f} eV")

if delta_E_zpe < 0:

print(f"\n ✓ Reaction is exothermic (C+O recombination favorable)")

else:

print(f"\n ⚠ Reaction is endothermic (dissociation favorable)")

3. Reaction Energy (C* + O* → CO*):

============================================================

Electronic Energies:

Initial (C*+O*): RPBE = -465.99 eV, D3 = -36.90 eV, Total = -502.89 eV

Final (CO*): RPBE = -467.14 eV, D3 = -36.82 eV, Total = -503.97 eV

Reaction Energies (without ZPE):

ΔE(RPBE only): -1.16 eV = -111.5 kJ/mol

ΔE(D3 contrib): 0.08 eV = 7.3 kJ/mol

ΔE(RPBE+D3): -1.08 eV = -104.2 kJ/mol

Computing ZPE for CO*...

ZPE(CO*): 0.18+0.00j eV (182.9+0.0j meV)

Computing ZPE for C* and O*...

ZPE(C*+O*): 0.18+0.00j eV (175.9+0.0j meV)

Reaction Energy (with ZPE):

ΔE(electronic): -1.08 eV = -104.2 kJ/mol

ΔZPE: 0.01+0.00j eV = 0.7+0.0j kJ/mol (6.9+0.0j meV)

ΔE(total): -1.07+0.00j eV = -103.5+0.0j kJ/mol

Summary:

Without D3, without ZPE: -1.16 eV = -111.5 kJ/mol

With D3, without ZPE: -1.08 eV = -104.2 kJ/mol

With D3, with ZPE: -1.07+0.00j eV = -103.5+0.0j kJ/mol

============================================================

Comparison with Paper (Table 5):

Paper (DFT-D3): -142.7 kJ/mol = -1.48 eV

This work: -103.5+0.0j kJ/mol = -1.07+0.00j eV

Difference: 0.41 eV

✓ Reaction is exothermic (C+O recombination favorable)

Step 5: Calculate CO Adsorption Energy (Bonus)#

Calculate how strongly CO binds to the surface:

print(f"\n4. CO Adsorption Energy ( CO(g) + * → CO*):")

print(" This helps us understand CO binding strength")

# CO(g)

co_gas = Atoms("CO", positions=[[0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 1.15]])

co_gas.center(vacuum=10.0)

co_gas.set_pbc([True, True, True])

co_gas.calc = base_calc

opt = LBFGS(co_gas, logfile=None)

opt.run(fmax=0.05, steps=relaxation_steps)

E_co_gas_ml = co_gas.get_potential_energy()

co_gas.calc = d3_calc

E_co_gas_d3 = co_gas.get_potential_energy()

E_co_gas = E_co_gas_ml + E_co_gas_d3

print(

f" CO(g): E_total = {E_co_gas:.2f} eV (RPBE: {E_co_gas_ml:.2f}, D3: {E_co_gas_d3:.2f})"

)

# Calculate ZPE for CO(g)

co_gas.calc = base_calc

vib_co_gas = Vibrations(co_gas, indices=[0, 1], delta=0.01, nfree=2)

vib_co_gas.clean()

vib_co_gas.run()

vib_energies_co_gas = vib_co_gas.get_energies()

zpe_co_gas = 0.5 * np.sum(vib_energies_co_gas[vib_energies_co_gas > 0])

vib_co_gas.clean()

print(f" ZPE(CO(g)): {zpe_co_gas:.2f} eV")

print(f" ZPE(CO*): {zpe_co:.2f} eV (from Step 4 calculation)")

# Electronic adsorption energy

E_ads_co_elec = E_final_co - E_clean - E_co_gas

# ZPE contribution to adsorption energy

delta_zpe_ads = zpe_co - zpe_co_gas

# Total adsorption energy with ZPE

E_ads_co_total = E_ads_co_elec + delta_zpe_ads

print(f"\n Electronic Energy Breakdown:")

print(f" ΔE(RPBE only) = {(E_final_co_ml - E_clean_ml - E_co_gas_ml):.2f} eV")

print(f" ΔE(D3 contrib) = {((E_final_co_d3 - E_clean_d3 - E_co_gas_d3)):.2f} eV")

print(f" ΔE(RPBE+D3) = {E_ads_co_elec:.2f} eV")

print(f"\n ZPE Contribution:")

print(f" ΔZPE = {delta_zpe_ads:.2f} eV")

print(f"\n Total Adsorption Energy:")

print(f" ΔE(total) = {E_ads_co_total:.2f} eV = {E_ads_co_total*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol")

print(f"\n Summary:")

print(

f" E_ads(CO) without ZPE = {-E_ads_co_elec:.2f} eV = {-E_ads_co_elec*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol"

)

print(

f" E_ads(CO) with ZPE = {-E_ads_co_total:.2f} eV = {-E_ads_co_total*96.485:.1f} kJ/mol"

)

print(

f" → CO binds {abs(E_ads_co_total):.2f} eV stronger than H ({abs(E_ads_co_total)/0.60:.1f}x)"

)

4. CO Adsorption Energy ( CO(g) + * → CO*):

This helps us understand CO binding strength

CO(g): E_total = -14.43 eV (RPBE: -14.42, D3: -0.01)

ZPE(CO(g)): 0.13+0.00j eV

ZPE(CO*): 0.18+0.00j eV (from Step 4 calculation)

Electronic Energy Breakdown:

ΔE(RPBE only) = -1.84 eV

ΔE(D3 contrib) = -0.24 eV

ΔE(RPBE+D3) = -2.08 eV

ZPE Contribution:

ΔZPE = 0.05-0.00j eV

Total Adsorption Energy:

ΔE(total) = -2.03-0.00j eV = -195.6-0.0j kJ/mol

Summary:

E_ads(CO) without ZPE = 2.08 eV = 200.5 kJ/mol

E_ads(CO) with ZPE = 2.03+0.00j eV = 195.6+0.0j kJ/mol

→ CO binds 2.03 eV stronger than H (3.4x)

Comparison with Paper Results

The paper reports a CO adsorption energy of 1.82 eV (175.6 kJ/mol) in Table 4, calculated using DFT (RPBE functional).

These results show:

Without ZPE: The electronic binding energy matches well with DFT predictions

With ZPE: The zero-point energy correction reduces the binding strength slightly

D3 Dispersion: Contributes to stronger binding due to van der Waals interactions

Step 6: Find guesses for nearby initial and final states for the reaction#

Now that we have an estimate on the reaction energy from the best possible initial and final states, we want to find a transition state (barrier) for this reaction. There are MANY possible ways that we could do this. In this case, we’ll start with the *CO final state and then try and find a nearby local minimal of *C and *O, by fixing the C-O bond distance and finding a nearby local minima. Note that this approach required some insight into what the transition state might look like, and could be considerably more complicated for a reaction that did not involve breaking a single bond.

print(f"\nFinding Transition State Initial and Final States")

print(" Creating initial guess with stretched C-O bond...")

print(" Starting from CO* and stretching the C-O bond...")

# Create a guess structure with stretched CO bond (start from CO*)

initial_guess = final_co.copy()

# Set up a constraint to fix the bond length to ~2 Angstroms, which should be far enough that we'll be closer to *C+*O than *CO

co_indices = np.where(initial_guess.get_tags() == 2)[0]

# Rotate the atoms a bit just to break the symmetry and prevent the O from going straight up to satisfy the constraint

initial_slab = initial_guess[initial_guess.get_tags() != 2]

initial_co = initial_guess[initial_guess.get_tags() == 2]

initial_co.rotate(30, "x", center=initial_co.positions[0])

initial_guess = initial_slab + initial_co

initial_guess.calc = FAIRChemCalculator(predictor, task_name="oc20")

# Add constraints to keep the CO bond length extended

initial_guess.constraints += [

FixBondLengths([co_indices], tolerance=1e-2, iterations=5000, bondlengths=[2.0])

]

try:

opt = LBFGS(

initial_guess,

trajectory=output_dir / part_dirs["part6"] / "initial_guess_with_constraint.traj",

)

opt.run(fmax=0.01)

except RuntimeError:

# The FixBondLength constraint is sometimes a little finicky,

# but it's ok if it doesn't finish as it's just an initial guess

# for the next step

pass

# Now that we have a guess, re-relax without the constraints

initial_guess.constraints = initial_guess.constraints[:-1]

opt = LBFGS(

initial_guess,

trajectory=output_dir

/ part_dirs["part6"]

/ "initial_guess_without_constraint.traj",

)

opt.run(fmax=0.01)

Finding Transition State Initial and Final States

Creating initial guess with stretched C-O bond...

Starting from CO* and stretching the C-O bond...

Step Time Energy fmax

LBFGS: 0 23:01:51 -466.820814 0.933386

LBFGS: 1 23:01:52 -461.473533 4.201399

LBFGS: 2 23:01:52 -461.541569 3.819022

LBFGS: 3 23:01:52 -461.870045 0.990589

LBFGS: 4 23:01:52 -461.937244 0.981921

LBFGS: 5 23:01:52 -461.962917 0.956283

LBFGS: 6 23:01:52 -461.954811 0.755221

LBFGS: 7 23:01:53 -462.007534 0.444253

LBFGS: 8 23:01:53 -461.961218 0.403348

LBFGS: 9 23:01:53 -462.022161 1.000305

LBFGS: 10 23:01:53 -462.031080 0.415334

LBFGS: 11 23:01:53 -462.046242 0.494780

LBFGS: 12 23:01:54 -462.085886 0.663025

LBFGS: 13 23:01:54 -462.161575 1.372185

LBFGS: 14 23:01:54 -462.215290 1.927856

LBFGS: 15 23:01:54 -462.263727 2.370239

LBFGS: 16 23:01:54 -462.341347 3.287233

LBFGS: 17 23:01:55 -462.304025 3.993962

LBFGS: 18 23:01:55 -462.370334 3.819039

LBFGS: 19 23:01:55 -462.478641 3.378005

LBFGS: 20 23:01:55 -462.646381 2.570744

LBFGS: 21 23:01:55 -462.936364 0.888155

LBFGS: 22 23:01:55 -462.968499 0.692334

LBFGS: 23 23:01:56 -462.997117 0.657991

LBFGS: 24 23:01:56 -463.056911 0.824350

LBFGS: 25 23:01:56 -463.096682 0.662722

LBFGS: 26 23:01:56 -463.107582 0.417180

LBFGS: 27 23:01:56 -463.109198 0.332080

LBFGS: 28 23:01:57 -463.141987 0.453317

LBFGS: 29 23:01:57 -463.165894 0.603940

LBFGS: 30 23:01:57 -463.165788 0.368804

LBFGS: 31 23:01:57 -463.200312 0.322940

LBFGS: 32 23:01:57 -463.208141 0.427666

LBFGS: 33 23:01:58 -463.222295 0.347186

LBFGS: 34 23:01:58 -463.251592 0.350275

LBFGS: 35 23:01:58 -463.240187 0.542475

LBFGS: 36 23:01:58 -463.252578 0.679913

LBFGS: 37 23:01:58 -463.289138 0.325561

LBFGS: 38 23:01:58 -463.296719 0.405574

LBFGS: 39 23:01:59 -463.301332 0.327242

LBFGS: 40 23:01:59 -463.310212 0.394633

LBFGS: 41 23:01:59 -463.342774 0.684987

LBFGS: 42 23:01:59 -463.396908 1.041083

LBFGS: 43 23:01:59 -463.432366 1.025362

LBFGS: 44 23:02:00 -463.502002 0.867384

LBFGS: 45 23:02:00 -463.554373 0.723542

LBFGS: 46 23:02:00 -463.617417 0.567341

LBFGS: 47 23:02:00 -463.638478 0.463407

LBFGS: 48 23:02:00 -463.702004 0.548109

LBFGS: 49 23:02:01 -463.751232 0.413914

LBFGS: 50 23:02:01 -463.804469 0.561162

LBFGS: 51 23:02:01 -463.828709 0.416286

LBFGS: 52 23:02:01 -463.866520 0.462146

LBFGS: 53 23:02:01 -463.927231 0.628401

LBFGS: 54 23:02:01 -463.985978 0.724530

LBFGS: 55 23:02:02 -464.037638 0.610976

LBFGS: 56 23:02:02 -464.063912 0.333690

LBFGS: 57 23:02:02 -464.066657 0.353587

LBFGS: 58 23:02:02 -464.083860 0.260285

LBFGS: 59 23:02:02 -464.110672 0.264590

LBFGS: 60 23:02:03 -464.119084 0.341915

LBFGS: 61 23:02:03 -464.126754 0.208025

LBFGS: 62 23:02:03 -464.129827 0.172884

LBFGS: 63 23:02:03 -464.129852 0.139661

LBFGS: 64 23:02:03 -464.140665 0.269152

LBFGS: 65 23:02:04 -464.140896 0.190554

LBFGS: 66 23:02:04 -464.145262 0.086952

LBFGS: 67 23:02:04 -464.148369 0.099588

LBFGS: 68 23:02:04 -464.150273 0.092913

LBFGS: 69 23:02:04 -464.157723 0.143432

LBFGS: 70 23:02:05 -464.155240 0.129300

LBFGS: 71 23:02:05 -464.155970 0.096974

LBFGS: 72 23:02:05 -464.160528 0.079164

LBFGS: 73 23:02:05 -464.158362 0.064338

LBFGS: 74 23:02:05 -464.158756 0.065502

LBFGS: 75 23:02:05 -464.153729 0.112244

LBFGS: 76 23:02:06 -464.160126 0.100987

LBFGS: 77 23:02:06 -464.157697 0.089216

LBFGS: 78 23:02:06 -464.158551 0.053670

LBFGS: 79 23:02:06 -464.152687 0.089649

LBFGS: 80 23:02:06 -464.160678 0.062396

LBFGS: 81 23:02:07 -464.163423 0.044126

LBFGS: 82 23:02:07 -464.159690 0.029514

LBFGS: 83 23:02:07 -464.157348 0.048974

LBFGS: 84 23:02:07 -464.160700 0.030442

LBFGS: 85 23:02:07 -464.163510 0.048193

LBFGS: 86 23:02:08 -464.164165 0.043521

LBFGS: 87 23:02:08 -464.161469 0.011285

LBFGS: 88 23:02:08 -464.156125 0.068748

LBFGS: 89 23:02:08 -464.160933 0.020223

LBFGS: 90 23:02:08 -464.163947 0.046041

LBFGS: 91 23:02:08 -464.159317 0.031542

LBFGS: 92 23:02:09 -464.159557 0.022492

LBFGS: 93 23:02:09 -464.161383 0.009039

Step Time Energy fmax

LBFGS: 0 23:02:09 -464.161383 0.471430

LBFGS: 1 23:02:09 -464.167315 0.444832

LBFGS: 2 23:02:09 -464.194849 0.877090

LBFGS: 3 23:02:09 -464.207762 0.494773

LBFGS: 4 23:02:10 -464.229632 0.356215

LBFGS: 5 23:02:10 -464.253263 0.423533

LBFGS: 6 23:02:10 -464.260134 0.331348

LBFGS: 7 23:02:10 -464.272953 0.265914

LBFGS: 8 23:02:10 -464.277216 0.242685

LBFGS: 9 23:02:11 -464.286119 0.165645

LBFGS: 10 23:02:11 -464.287936 0.100330

LBFGS: 11 23:02:11 -464.288964 0.086082

LBFGS: 12 23:02:11 -464.289786 0.095618

LBFGS: 13 23:02:11 -464.290871 0.098506

LBFGS: 14 23:02:11 -464.291574 0.073742

LBFGS: 15 23:02:12 -464.291964 0.049766

LBFGS: 16 23:02:12 -464.292238 0.065252

LBFGS: 17 23:02:12 -464.292587 0.072632